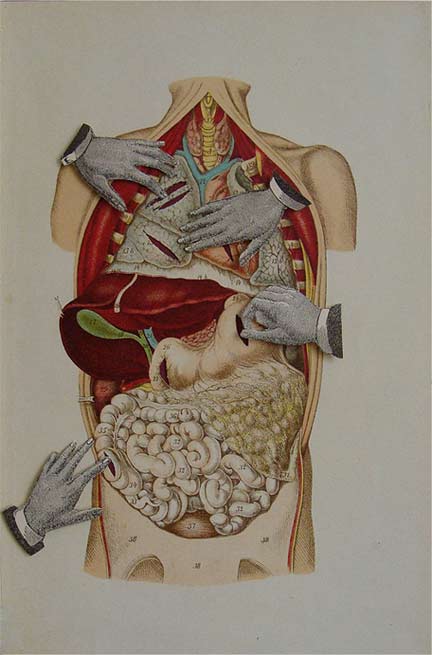

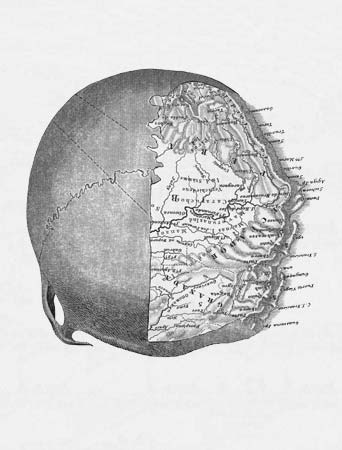

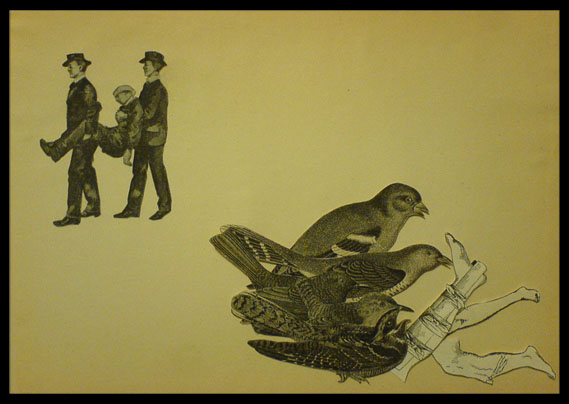

Wounds (2007)

Nicole Natri

I ran across this collage by the talented Nicole Natri shortly after attending an interesting lecture, “When Sleeping Beauty Walked Out of the Anatomy Museum,” by Kathryn Hoffmann, who is a professor of French at the University of Hawai’i at Manoa. The connection here is pretty cool, but it’s roundabout, so bear with me.

Dr. Hoffmann’s talk was my introduction to Pierre Spitzner’s traveling museum, the “Musee Spitzner”: a collection of anatomical models, moulages, specimens, paintings, dioramas, etc., that toured Europe for about a century before being dismantled circa WW2. Some of the Spitzner pieces ended up at the University of Paris, but unfortunately many others are now lost. The Spitzner’s centerpiece was a wax anatomical model of a sleeping woman, which opened to reveal her internal organs – much like the Anatomical Venus by Susini at La Specola, but simpler in execution. Unlike Susini’s model, however, the Spitzner Venus had a mechanical movement intended to emulate breath: her chest rose and fell as she lay there in her white nightgown. That’s a dramatic dissolution of the distinction between life, sleep, and death – and with its vivisectionist overtones, quite disturbing!

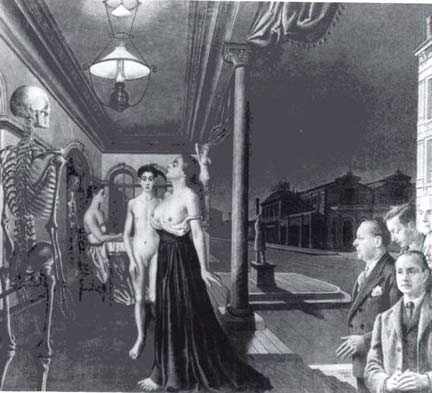

As if the breathing, sleeping Venus wasn’t interesting enough in her own right, the Surrealist painter Paul Delvaux, known for depicting languid naked (or nightgowned) women wandering the streets of Paris, was heavily influenced by the Spitzner collection (as mentioned in a recent post over at Morbid Anatomy). He encountered it at the Brussels Fair in 1932. Delvaux painted the Spitzner itself several times (The Musee Spitzner, 1943, below), but I didn’t realize until Professor Hoffmann’s talk how direct the connection is.

Compare Delvaux’ Sleeping Venus (1944) to Susini’s Anatomical Venus (the Spitzner’s wax Venus did not look exactly like this, but was probably close). Then compare The Musee Spitzner (as David Scott recommends in his book, Surrealizing the Nude) to Wiertz’ La Belle Rosina (1847):

The Sleeping Venus (1944)

Paul Delvaux

Anatomical Venus

Clemente Susini

Musee Spitzner (reproduction; original destroyed; 1943)

Paul Delvaux

La Belle Rosina (1847)

Antoine Wiertz

I always thought all these skeletons and somnambulant nudes were simply Delvaux’s bizarre imagination run amok. But it appears Delvaux was just as obsessed with, and influenced by, medical curiosities as we are today. (Life and death, you know – heavy stuff!)

In The Musee Spitzner this [juxtaposition of living structure and emblem of death] is achieved by the creation of a masterly confluence of related themes. First, there is the almost scientific interest Delvaux shows, like so many figurative painters, in the structure of the human body, both in its skeletal form and in its musculature (Delvaux had studied his Vesalius). The skinned male thus appears in The Musee Spitzner, as it appears the following year in another version of the Sleeping Venus, in which it stands before wall-charts illustrating various aspects of the male anatomy. (Surrealizing the Nude, David Scott; the ecorche, or skinned male specimen, Scott describes is in the back left of The Musee Spitzner, and unfortunately barely visible behind the seated woman in the image above.)

So how do we circle back to that Nicole Natri collage, Wounds, at the beginning of the post? Well, another fascinating thing Dr. Hoffmann shared about the Spitzner was that many of the wax surgical models, particularly the obstetrics models, were festooned with disembodied surgical hands! No arms, just cuffed wrists and hands, “operating” on the models. Yikes! I think I find this image more disturbing than the “breathing” wax Venus.

Most anatomical models I’ve seen are arranged cleanly, even elegantly, as if they had always been so – without blood or signs of surgery. A few obligingly hold their bodies open, or pose to show their innards to the viewer: fantasies that pleasantly veil the reality of death. (See my previous post on this topic for examples). But disembodied, foreign hands opening the body for the viewer evoke both the messy, unaesthetic surgery that is really required to reveal those inner structures, and the undeniable fact that, fantasy aside, the body itself is not in control of its own revealing. No matter how drowsy, ecstatic, or peaceful the Venuses look, they’re invaded – if only by our eyes. The hands make that invasion overt; the anonymity of the hands makes them universal. How many hands, over the years, have opened Susini’s Venus, and unfolded her organs? Is invasion the ominous force that permeates Delvaux’s Sleeping Venus – who lies oblivious, while her distraught doppelgangers wail?

Nicole’s piece captures my own disquiet perfectly. The disembodied hands and surgical implements are black-and-white, from another world than the technicolor body underneath them. Their intentions seem ambiguous. Are they clinical, or just curious? And what’s our excuse for looking, anyway?

More:

Kathryn Hoffmann’s 2006 article, “Sleeping Beauties in the Fairground,” in Early Popular Visual Culture