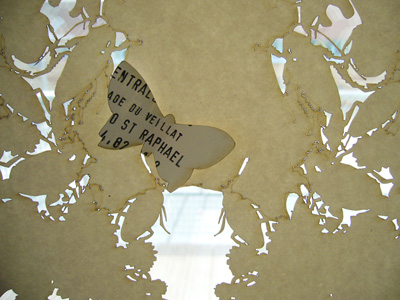

Swarm (detail)

mixed media

Tessa Farmer, 2004

from the Saatchi Gallery

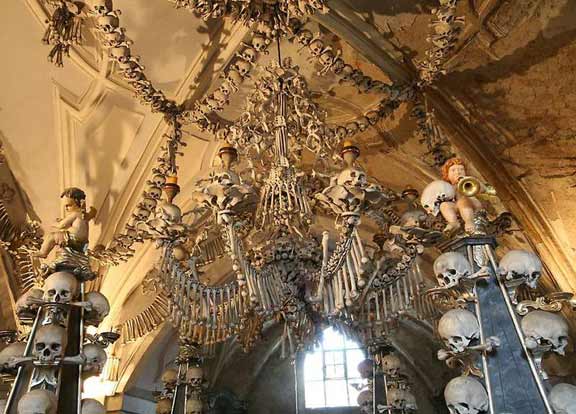

Before their nursery sanitization, fairy tales were savage. Remember how Cinderella’s stepmother mutilated her own daughters’ feet to fit the glass slipper, but was betrayed by the oozing blood? Or the rape and cannibalism in early versions of Sleeping Beauty? If you don’t, then you haven’t read the oldest versions of these now toothless, Disneyfied stories. Fairy tales once captured the primal violence in human nature all too well.

Fairies themselves were often grotesque and inhumanly cruel, and that’s the pre-Victorian tradition to which the work of artist Tessa Farmer cleaves. Her work juxtaposes dead insects and the remains of birds and snakes with tiny, skeletal fairy sculptures so small, she needs a microscope to assemble them, and viewers need a magnifying glass to appreciate them. Unlike the rosy-cheeked, butterfly-winged fairy girls you find on greeting cards, Farmer’s corpselike fairies rip their prey apart bare-handed, gnawing on the legs of hapless insects like ravenous, humorless Gollums. I would normally find a dead, twisted spider corpse disgusting, but Farmer’s gremlins are far creepier than their victims.

Swarm (detail)

mixed media

Tessa Farmer, 2004

from the Saatchi Gallery

A 2006 review by Stephen Feeke describes Farmer’s later work, The Terror:

Talking with Tessa Farmer about her work made me think of spiteful little boys who delight in pulling the wings off daddy-long-legs (sic). Seemingly inexplicable, this kind of puerile cruelty actually creates an understanding of the natural world. Pulling something apart helps us to learn how it was put together and how it functioned; it teaches us about life and death and this knowledge helps us to assert our dominance over nature. . .

Farmer is at the centre of all this action. She is complicit in the behaviour of her fairies and yet oddly speaks as if she is removed from it. Distancing herself from the possible carnage the fairies are hatching, she delights in the suggestion that they have the potential to exist independently of her. In this way she heightens our experience of the work, encouraging us to believe it might all be possible and true. Bearing in mind what happened to Dr Frankenstein, however, presumably Farmer herself is at as much risk as the rest of us.

In the artist’s own words,

In 2005 I first observed parasitic behaviour among the fairies, which had shrunk to some 7mm tall. ‘Nymphidia’ (named after a sixteenth century fairy poem by Michael Drayton) is another swarm, again revealing scenes of torture and consumption. The focus of the attack is a wasps’ nest, surrounded by fairies battling with wasps and other insects. On closer inspection they can be seen hatching out of wasps in the cells of the nest, by pushing off their heads and climbing out of the hollow shell of the consumed wasp.

The interesting thing to me is that, in reviews and comments on Farmer’s work, and in her own statement, the violence is described in increasingly naturalistic, pseudo-scientific terms. Are these “fairies” or “parasites”? Are they out of nature, or embodying nature? Is Farmer-the-artist, like Dr. Frankenstein before her, a meticulous scientist who reanimates flesh in order to understand it, or a monomaniac blind to the moral implications of her creation? Tennyson’s “Nature, red in tooth and claw” never seemed so appropriate!

At dinner last night, I disgusted my companions by sharing the appalling reproductive habits of the mite Acarophenax tribolii (courtesy of the Evilutionary Biologist – I warn you, it’s icky). I wish I could claim I was inspired in this misbehavior by Halloween, but as a biologist, I wander into inappropriate dinner conversation all the time. I can’t help it, really. Thinking about it scientifically, objectively, blunts the horror that kicks in when one begins to instinctively anthropomorphize the mites. Curiosity dominates empathy, and fascination displaces disgust – at least for a time. Biology is full of violence and broken taboos, but these natural relationships carry only the moral baggage we bring to them. The mites don’t know how to live any other way, and judging them or reviling them for it is absurd.

The way Farmer speaks of her work, with clinical detachment, is an invitation to follow her into a morally neutral scientific space. She must know full well that the viewer will be unable to sustain that detachment, because her fairies are not mites. They’re nearly human. And we also empathize with the fairies’ helpless victims – birds, ladybugs, bees, even that unlucky spider, curled and twisted in attitudes of pain that are universal. So despite our best efforts to remain detached, we won’t. Like looking at an optical illusion that oscillates from an old woman to a young girl, or a vase to a pair of profiles, we’ll find ourselves identifying first with the victims, then with the cruel aggressors (in these battles, the fairies seem to rarely be at a disadvantage).

By doing this – by forcing human emotions onto her invented ecosystem – Farmer alludes to the destructive effect humans have had on our world. In the scene below, from Nymphidia, a corpselike fairy erupts from a parasitized honeycomb, snaring an unsuspecting wasp. Nymphidia predates the news of honeybee colony collapse disorder (CCD) – but isn’t it an appropriate representation? Some unknown force, which we may as well depict as a wasp-sized demon, is invading beehives and destroying colonies in the “real” world. This fairy is the wasp/bee Grim Reaper: fanciful, inaccurate, but standing in for a destructive force that actually exists. And it’s fitting that the tiny Reaper is anthropomorphic, because CCD is almost certainly is due to human influence: something in our husbandry practices is making the bees vulnerable.

Nymphidia (detail)

Mixed media

Tessa Farmer, 2005

via Miniature Worlds

In the end, Farmer’s art is barely about “fairies” at all. That is, it’s barely about Disneyfied fairies: Tinkerbell, wishes, magic, romance. It is, of course, very much about the cruel, atavistic fairies of the primal fairy tales – disturbing representations of the extremes of human nature. And it’s human nature that pits us against Nature.

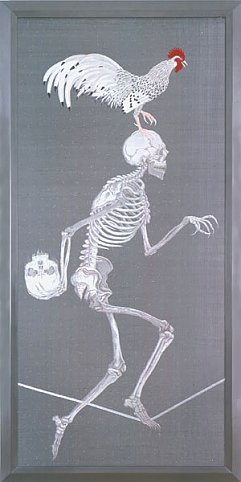

My lingering question about Farmer’s work is this: do the fairies know any better? Are they, like the mites, innocent by reason of insentience? Or are they, like the humans whose skeletons they mimic, not merely violent, but unnecessarily, deliberately cruel? I’d like, as a biologist, to embrace the former. But I think – based especially on her use of words like “torture” – that Farmer intends us to believe the latter. We are Farmer’s fairies. Nature, and we, suffer for it.