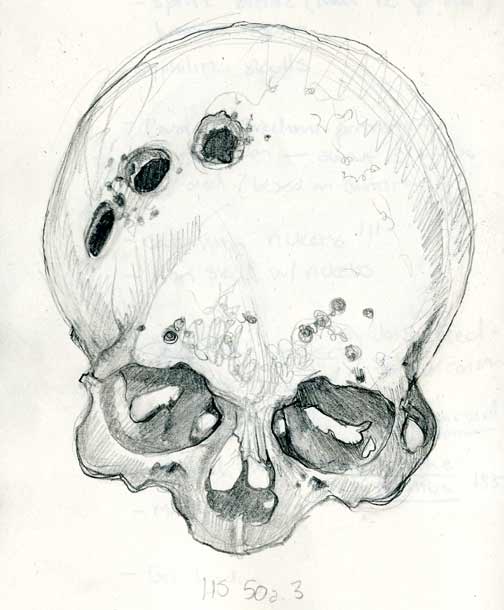

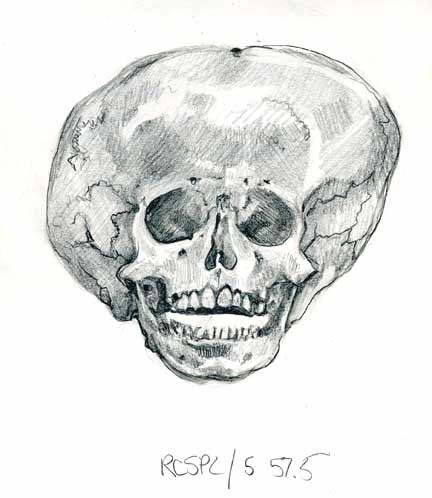

Syphilitic skull with three trephine holes and osteomyelitic lesions

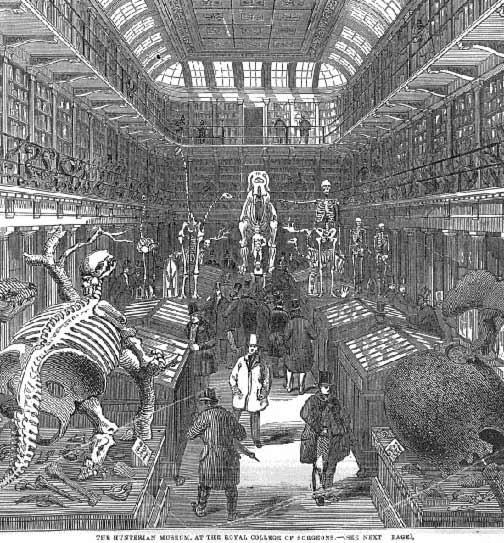

Hunterian museum

One of my favorite London experiences was my visit to the Hunterian museum. If only I had more time there! I liked it so much, I returned on my last day, procrastinating my departure for Heathrow as long as possible.

The Hunterian is tucked away inside the Royal College of Surgeons of England, on Lincoln’s Inn Fields. In its Victorian incarnation, it was a wonderful multi-tiered gallery with railings, balconies, and suspended skeletons:

Illustrated London News, 1845

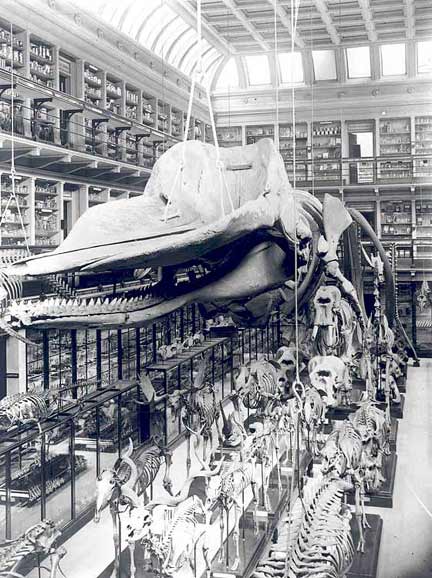

The Hunterian Gallery before the wars (source)

So I was shocked when I entered the grey, columned Royal College, climbed a graciously curving stairway, and found this extremely modern, two-story crystal-and-glass atrium:

The Crystal Gallery at the Hunterian Museum, Royal College of Surgeons

Definitely not what I was expecting! But it grew on me. I love ornate curiosity cabinets, but there is something very elegant about unadorned bones, and simple glass jars. Biological structures are so rich with intrinsic beauty, there’s no real need to gild the lily (that means you, Damien Hirst).

Though the new Hunterian galleries are peaceful and refined, I felt a slight pang of regret for the railings and wood cabinetry Darwin would have touched, when he studied here in the 1830s and 40s. Unfortunately, many of the specimens Darwin saw were destroyed when the Royal College of Surgeons was bombed in 1941. Like the gallery housing it, John Hunter’s collection is no longer what it once was. But what remains is still pretty darn amazing.

Hunter, a renowned surgeon and fellow of the Royal Society, worked tirelessly to collect medical anomalies like the 7’7″ skeleton of the Irish Giant, Charles Byrne (for which Hunter paid 130 pounds). He also amassed thousands of less exotic teaching specimens: though he did not have access to formaldehyde, he took wet preservation in alcohol to its highest level. After Hunter’s death in 1793, his ~13,000 specimens were purchased by the British state. The collection would be maintained (and enlarged) by the Royal College of Surgeons for the next two hundred years.

Hunter’s collection is organized according to some rather unusual curatorial precepts. As a physician and early experimentalist, Hunter was less interested in taxonomy than in physiology. He grouped specimens not by family or type, but as exemplars of processes – mouthparts and digestion, reproduction, etc. From the Victorian perspective,

The design of Mr. Hunter, in making this collection, was to exhibit the gradations of nature, from the most simple state in which life is found to exist, up to the most perfect and most complex of the animal creation, man himself. By his art, he was able to expose and preserve in a dried state, or in spirits, the corresponding parts of animal bodies; so that the various links in the chain of a perfect being may be readily followed and clearly understood. (Mogg’s New Picture of London and Visitor’s Guide to its Sights, 1844)

But Hunter’s collection does not exemplify linear progression, so much as ramification: the incredible diversity of ways that animal forms have evolved to accomplish given functions. Most of the specimens displayed here are not human; the Hunterian is a shrine not to Man, but to our entire extended family.

I first heard of the Hunterian through the delightful book Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture of Natural History Museums, by Stephen Asma at Columbia College, Chicago. (I highly recommend this book, if you don’t own it already). Asma’s first impression of the Hunterian was similar to my own:

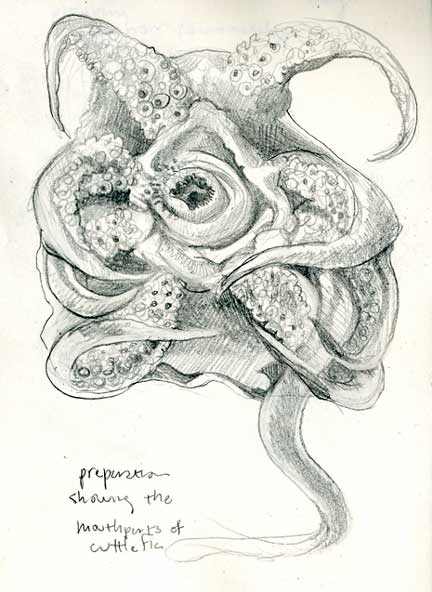

Without a grasp of Hunter’s underlying principles, the cases seemed slightly irrational. In one case, marked “Digestion,” I found various dissections of mammals, parasitic worms, a cicada, a locust, slugs, a squid, a vulture, a woodpecker, and a puffin. This hodgepodge arrangement follows no taxonomic grouping. . . Individual species, genera, and even families are displayed together to illustrate the unique ways that their structures fit the functions of digestion, circulation, respiration, and so forth. (Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads, 63)

My copy of Pickled Heads has been with in storage with the rest of my belongings for months, so I’d forgotten Asma’s words. But when I walked up to the first case of Hunter’s jars (mouthparts of squid, beaks, teeth, mouthparts of bees and cicadas), I immediately remembered Asma’s description, and recognized what he meant. The intestines of fish were right next to the stomachs of mammals, including a rat which substantially outweighed the tiny human fetus next to it. There is no mistaking the idiosyncratic style of this little museum, so different from the aggressively educational dioramas of the London Natural History Museum or the Smithsonian Natural History Museum. Modern biology museums are full-color, multimedia entertainment factories – it’s a way to engage the audience, true, but it sometimes teeters toward the tawdry and didactic. Asma expresses the difference far better than I could:

Perhaps the most notable aspect of the Hunterian Museum–besides the bleached and bloated “monsters”–is that it’s not intended for a lay audience. The Hunterian doesn’t really care whether the average person is “getting it.” This is unexpectedly unnerving, since most other museum encounters come complete with torrents of helpful information. Almost every museum specimen that you have ever encountered, be it a fossil, a jar, or a mount, is accompanied by a plaque, a chart, or a recording that announces to you–even before a question has been formulated in your head-“what you are seeing is so and so. . . .”

What was Hunter trying to communicate when he grouped his specimens? This question alone gives one a more interactive relationship with the museum than any computer gadgetry could. (Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads, 78-79)

It’s a little unfair to say the Hunterian doesn’t care if visitors “get it.” I saw a class of kids around twelve years old when I was there, moving in and out of a room set aside for teaching purposes, and they seemed to be “getting it” pretty well. The point is, they were being allowed to draw their own conclusions, and with a little guidance, to simply wander and wonder. Refreshing indeed.

What do I do when confronted with a mute collection of natural wonders? Why, break out the sketchbook. But I didn’t have one! It’s been so long since I felt peaceful enough to sketch in a museum – I’m normally buffeted by thousands of obnoxious children, and worse, tourists who act like children. I wasn’t prepared. I had to buy a little 5″x8″ Moleskine at a nearby bookshop, and sketch with a mechanical pencil while sitting on the floor. Since the museum does not allow photography, not even for earnest, sincere bloggers, these little doodles are all I have to represent Hunter’s myriad curiosities. I can’t believe I didn’t even get to the bound foot, or the lion with rickets, or the male and female ivory anatomical models. Argh.

Sepia officinalis (preparation showing the mouthparts of a cuttlefish)

Hunterian Museum

If you are active in the biomedical professions (and yes, they will ask for proof of this, like an ID card) you may also visit the Wellcome Anatomy and Pathology Museum upstairs.

At first glance, the Wellcome collection seems like the neglected younger sibling of the Hunterian prodigal son (or, if you prefer, the Harry-under-the-stairs to the spoiled Hunterian Dudley Dursley). It’s one outdated, drab room, filled with hundreds of specimen jars. No sexy lighting or pedagogical dioramas here – to figure out what you’re viewing you have to thumb through well-used, slightly sticky binders of notes. These binders are tucked in shelves or tables, wherever the last user left them; I couldn’t find one of the binders at all, so I’m still in the dark about some of the skeletal abnormalities I saw.

But the biggest difference is that the Wellcome specimens are all Homo sapiens, representing a variety of obscure, rare, or dramatic medical conditions – conditions, like keratin horns, that I never expected to personally see in the flesh! And they’re generally in better condition than the Hunterian specimens (most date from the 20th century). I could have spent five to ten minutes examining a single specimen, and there are hundreds of prosections in the Museum. I was completely overwhelmed, and didn’t sketch a single thing (sorry).

I wondered why the Hunterian and Wellcome collections were spatially isolated in this way, and the Wellcome closed to the public. It couldn’t be about shock value – some of the Hunterian exhibits were pretty gruesome. So I asked the head of conservation, who told me that it has to do with the legal status of the collection.

The UK has a long history of scandalous “body-snatching” (see this Curious Expeditions post for more on that nefarious activity). Since the 1832 Anatomy Act, enacted to discourage the illicit sale of body parts, specimens like those in the Wellcome collection have been more and more tightly restricted. Since 2006, the Human Tissues Authority has regulated the donation, disposal, and use of medical specimens and cadavers, and requires special licesning for the public display of remains from persons who died since 1906 (according to their FAQ, they also require licenses of plastination exhibits, such as Body Worlds). But since John Hunter lived, collected, and died years before the Anatomy Act, his collection can be displayed without the restrictions that impact the pathology collection.

Skull of 25-year-old man showing enlargement due to hydrocephalus

Liston collection at Hunterian Museum

I highly recommend both the Hunterian and Wellcome collections to any biologist, artist, kunstkammer fan, or interested layperson visiting London. The Hunterian is perfectly suitable for older children, and surprisingly peaceful for a (free!) museum so close to both the British Library and Inns of Court. There were tourists everywhere, but only a handful stopping by to see John Hunter’s life’s work. You might make a day of it and also visit the Wellcome Collection, around the corner near UCL, or Sir John Soanes Museum, which is literally across the street – but then, I still need to post about those, don’t I?

So much to see, so much to blog, so little time. What a wonderful world.

Your “little doodles” are wonderful!

Thanks for the tour of the Hunterian – I’d love to see more!

Wait…those are your drawings, Cicada? Very nice, indeed.

Those are really amazing sketches, and a perfect post on the reason that science museums can sometimes be so lacking in wonder and places like the Huntarian so full of it. I am however gonna have to figure out how to get around that ID card business…

Oh my goodness, the Hunterian is at the top of my museum list…I read about it in ‘Pickled Heads’ too. I LOVE that book! I imagined it would always be dusty and dark…is the rooster with a tooth in his head still around?

Excellent post (I especially liked your Damien Hirst reference :)) !

I’ve said it before, but I’ll say it again — it is uncanny just how much we have in common!

PS: ‘Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads’ is one of my all time favourite books!

PPS: awesome sketches!!

I adore your sketch of the trepanned skull. I would frame that and hang it on my wall.

Pingback: bioephemera.com » London: the Icky Tour

Great sketches. I’ve been trying to find the name of this museum for some time, all I knew was that it was around Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Today was my day for detective work, I’m glad I found your article as its just confirmed how much I want to go.

p.s. If you still like museums that have the wooden sides you should try Ipswich museum in suffolk – really good.

I visited the museum today, it was great! Your drawing of the skull looks identical to what I saw today.

I visited the museum today, it was great! Your drawing of the skull looks identical to what I saw today.

I had the great pleasure of spending several days at the Hunterian at the end of last January. A splendid – but as you described – frustrating place. One could spend a lifetime trying to work out the system of Hunter’s displays; but what I found more curious were some of the modern curatorial ideas, such as placing Caroline Crachami’s (the Sicilian Fairy) skeleton in a display about teeth! Yes, yes – recent dental investigation has shown that she was probably only 3, not 25-years-old; but fer crissakes, the most interesting bit about her is her tiny stature, not her teeth (and besides, a cursory glance at her sternum tells the tale anyway). I did do a number of drawings there, which will be unveiled shortly as part of my “Cabinet of Curiosites” project (www.mundieart.com/cabinet). I can hardly wait to return.

Thansk so much for posting this. I can’t remember how I came across your blog, but after seeing this post I decided I’d have to visit the Huntarian Museum. I have now discovered a website listing medical musuems here in London and decided to explore them all. I had no idea these places existed!

I went to the Huntarian Museum today. It’s very pretty with all those glass cabinets and things in jars. I also sketched the skull showing severe hydrocephalus, although with less artistic talent! I must have missed the trepanned skull. There’s so much there it’s overwhelming.