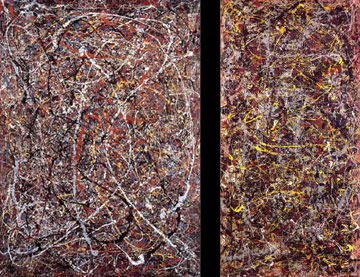

One: No. 31, 1950

Jackson Pollock, 1950

MoMA, NYC

A piece from Sunday’s New York Times announced a break in the ongoing controversy over 32 disputed Jackson Pollock paintings. The paintings were reportedly found in a storage unit in 2002 by Alex Matter, the son of Pollock’s friend, Herbert Matter. The putative Pollocks looked like Pollocks to experts (including Case Western art professor Ellen Landau), but a team of conservation scientists from Harvard University Art Museums concluded a week ago that they were probably not authentic. The analysis (conducted pro bono at Matter’s request) found pigments in three of the paintings which were not patented or available in the US until after Pollock’s death (the paintings were dated 1946-49; Pollock died in 1956). But is this really the verdict of “Science”?

Pollock authentication has been a hot topic for a few years. Richard Taylor, a physics professor at the University of Oregon, published a 2006 Nature study on six of the disputed Pollocks. He objected that they lacked a fractal geometry he had previously identified in 14 verifiable Pollocks. Taylor also said that the high variability in pattern between the paintings suggested they had been done by several different artists.

But Katherine Jones-Smith, a physics grad at Case, released her own Nature paper in November, in which she showed that her own intentionally rudimentary scribbles of stars were “fractal” enough to meet Taylor’s definition of a Pollock (Taylor disputes this). She also questioned the mathematical validity of applying fractal analysis to the paintings because of the relatively narrow size range between the individual paint drops and the entire painting.

Untitled 5

Katherine Jones-Smith

Amusingly, Jones-Smith says she originally didn’t think anyone would still care about her critique of Taylor’s work, because his original fractal study was several years old. But there’s a great financial incentive to prove these paintings are Pollocks. An undisputed Pollock recently sold for $140 million.

Of course, any study can be nitpicked. A major problem is sample size: Taylor looked at only 6 of the disputed Pollocks, while the Harvard study examined only 3. The Harvard study noted that all of the disputed paintings had been significantly restored, and while they believe that would not have adulterated the composition of paint in the original layers of the piece, it does provide an opening for Alex Matter and his advocates. Further, the paintings were labeled “experimental” (in what appears to be Herbert Matter’s authentic handwriting). If Pollock was playing around and experimenting with technique, is it fair to expect his paintings to closely resemble his known work? Could he have obtained unusual paints with which to experiment (perhaps, as Matter has suggested, from Europe)? What sort of assumptions can we make about the behavior of an artist in executing his or her work?

Next on the Pollock rollercoaster: the 15 minutes of fame Teri Horton experienced last year, when she bought a $5 painting in a thrift store in California. She thought it might be a Pollock. After appearing on Letterman to describe her experience, she starred in a documentary entitled “Who the #$&% Is Jackson Pollock?” The film details her efforts to authenticate her painting, down to a possibly million-dollar fingerprint on its back.

(L-R) Teri Horton’s disputed Pollock (66 3/4″ x 47 5/8″); David Geffen’s $140 million Jackson Pollock No. 5 (48″ X 96″).

I admit, I’m not a huge Pollock fan. What I’ve been enjoying most about this controversy is the way everyone is spinning it as some type of art vs. science showdown. Here are some examples just from Sunday’s NYT:

Alex Matter (Pollock/Matters press release):

“The authentication of works of art is still more art than science. Scientific analysis can attempt to eliminate a work of art as genuine, but it can’t determine if it is indeed the work of any given artist. That has been, and remains, the job of the scholar.â€

I like how this statement recognizes falsifiability as the central characteristic of scientific investigation. But dude, aren’t scientists scholars too? Also, I think the word “art” sneakily shifts definition within the first sentence. . .

Naryan Khandakar of the Harvard team:

“I think it’s very much dismissing information because it’s inconvenient for their arguments,†he said, adding that such an approach to scholarly debate is “a little like Stephen Colbert’s concept of truthiness, where you’re almost there but you don’t have the whole thing.”

“Inconvenient” and a shout-out to Colbert? Snap! Who’s in touch with the zeitgeist? But though you have dazzled me, I’m not sure what you mean. (I’m almost there, but I don’t have the whole thing.)

Helen Landau:

“I can’t construct an alternate scenario that makes any sense. Science might not be wrong, but the research behind it might not be a 100 percent correct. And so more research needs to be done.â€

Science might not be wrong, but the research might not be right. Huh? Science is, by definition, never 100% certain. And what exactly is the difference between science and research here? I’m confused. More research always needs to be done.

I suspect that these experts would make a lot more sense if they weren’t being edited for mainstream media.

Here’s one more:

“It is impossible to make a forgery of Jackson Pollock’s work. He had an almost preternatural control over those skeins of paint.”

That’s Time Magazine’s art critic, Robert Hughes. In 1982. If the Harvard team is right, Hughes was wrong.

Go here to forge your very own Pollock! (I don’t know if it’s even slightly fractal).

Terrific post! Funny ‘cuz it’s true…or is it?