From “Making the Step from Chemistry to Biology and Back,” Nature Chemical Biology

David Goodsell

The Nov/Dec issue of Seed features an interesting article by Jonah Lehrer on science and art. It’s a short read, but it touches on most of the big issues at that intersection, primarily through the lens of neurobiology.

I haven’t read Jonah’s new book, Proust Was a Neuroscientist, and I’m probably not going to get around to it for a while, if the half-dozen half-read books around my apartment are any indication (News flash: Machiavelli and Stephen Pinker are vying with John McPhee for the top of the heap)! I’m going to assume that the scanty arguments in the article are fleshed out further in the book, which is getting good reviews. But I have some quibbles.

The point of the article is solid: art can, and should, inform science, and both are necessary to answer “the deepest questions” of human experience. My first response was, well, duh. But I understand that to a lot of people, this isn’t necessarily intuitive. Science is so well-defined, and art is so, you know, fuzzy!

Jonah plays into that cliche:

. . . this rigorous science had no need for Jamesian vagueness. It wanted to purge itself of anything that couldn’t be measured. The study of experience was banished from the laboratory.

But artists continued creating their complex simulations of consciousness. They never gave up on the ineffable, or detoured around experience because it was too difficult. They plunged straight into the pandemonium.

I like “plunged straight into the pandemonium”: what a great description of the human mind in all its messy, noisy glory (that goes equally for an EEG, a whole-genome association study, or a Pollock). But what’s up with this anthropomorphizing of “science”? And later in the article: “Neuroscience, of course, believes it has no inherent limitations.” I don’t know; I haven’t spoken with Neuroscience lately – but I bet Jonah hasn’t either.

Neither science nor its moody teenage spawn neuroscience can want or believe anything – that’s just fuzzy language. It wouldn’t be a big deal, except that it’s also one way in which creationists and others denigrate science: by insinuating that science is an entity with an implicit, inextricable agenda to devalue the entire non-scientific realm (including both art and faith). Just as we have a responsibility to use the word “theory” carefully, because we know its weight, we must consistently distinguish the process of science from the agendas and prejudices of the flawed human beings who practice it.

I know no neuroscientists (say that three times fast) who claim neuroscience is without limitations. Personally, I believe human understanding in its entirety has fundamental, biological constraints – and at least for the foreseeable future, the practical power of neuroscience is thus constrained as well. Jonah asserts that art can extend our understanding past those constraints, through metaphor and analogy – a point I made myself in a short essay last spring, and one I fully agree with. Einstein’s thought experiments were brilliant launching points for his science. But to me, art isn’t part of science. Art may help us decide where to point our scientific searchlight, but it’s just a first step – the intuition that sets the detective on the right path, not the evidence, and definitely not the crime lab.

That’s where I begin to disagree with the message of this article – I don’t think that art is necessary for the practice of good science. I think art complements science in the human experience, and inspires humans who do science. According to the article, “We need to find a place for the artist within the experimental process. . . it’s time for the dialogue between our two cultures to become a standard part of the scientific method.” I think that’s a huge overstatement. I used to teach the scientific method, and I’m not sure where I’d put “art” in the flowchart. At the beginning, I suppose, as an inspiration for hypothesis formation – alongside other inspirations like nature, dreams, falling apples, or finding only one sock in the dryer. When it comes to informing science, is art really privileged over other aspects of the complex human experience?

When Jonah says, “the arts are an incredibly rich data set,” he’s absolutely right. And he’s right that artists discovered and exploited many of the basic principles of our visual systems:

As the neuroscientist Semir Zeki notes, “Artists [painters] are in some sense neurologists, studying the brain with techniques that are unique to them.” Monet’s haystacks appeal to us, in part, because he had a practical understanding of color perception. The drip paintings of Jackson Pollock resonate precisely because they excite some peculiar circuit of cells in the visual cortex. These painters reverse-engineered the brain, discovering the laws of seeing in order to captivate the eye.

But if you “reverse-engineer” something, doesn’t that imply you understand its mechanism? To claim artists understand the visual system because they can harness its rules to good effect. . . that’s a big leap. Good cooks aren’t often able to explain chemistry, and athletes don’t necessarily understand either physics or physiology.

Even if art can be defined as a process of investigation, for the creator and the viewer, the discoveries it yields are inarticulate, unquantifiable, irreducible – that’s why we have art in the first place. Just try to get all the people in a gallery to agree on what they see in an abstract painting, much less why they feel about it as they do. Scientists like Zeki and Ramachandran study the effects artistic elements have on the brain, but they don’t embed their results in yet another piece of art.

In this essay, Jonah seems to argue that because art is irreducibly contradictory, like the human mind, art is therefore necessary to help science unpack the mind. I guess it’s the principle that “like dissolves like”? I’m not sure that’s what he really means to say; I think he was hobbled by the brevity of the assignment. But it was a nice read, and it did have a highly entertaining moment:

Every theoretical physics department should support an artist-in-residence. Too often, modern physics seems remote and irrelevant, its suppositions so strange they’re meaningless. The arts can help us reattach physics to the world we experience.

Plug “modern art” in for “modern physics”. The sentence works even better now! Ha. Expecting modern art, which most people don’t get in the first place, to make science more comprehensible is like . . . expecting a child’s balloon to steer a dirigible! (OK, I have no idea what that sentence means. I was trying to expand my limited understanding of reality through metaphor, and went fatally awry.)

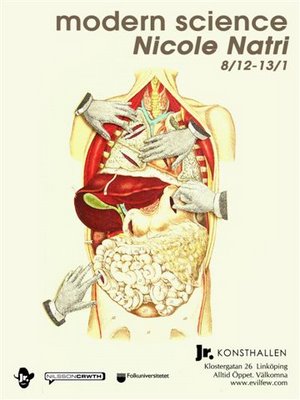

So what place does art have in science? It enhances creativity. It helps us see things with new eyes – prompting us to ask new questions or resolve intractable problems. In the quantitatively inclined, it maintains a healthy left-brain/right-brain balance: most scientists I know are either artists or musicians (I may have a biased data set). And because art vaults right over jargon and equations, it’s the best tool we have for sharing complex scientific concepts with nonspecialists, or for “re-phrasing” what we know, so we can consider it from a new angle.

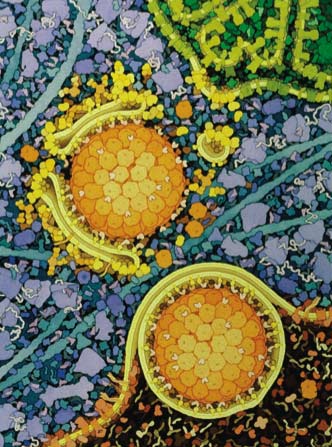

Consider this recent Nature Chemical Biology article by David Goodsell (Nov 2007), from which the lovely image at the top of the post is taken. Goodsell emphasizes the power of art as a scientific tool:

Pictures are powerful: they radically shape how we think about the subjects that we study. Think of Jane Richardson’s ribbon diagrams, and the way they have shaped our thinking about proteins. The clear and compelling nature of these ribbon diagrams spawned an entire discipline of folding classification and taxonomy. . .

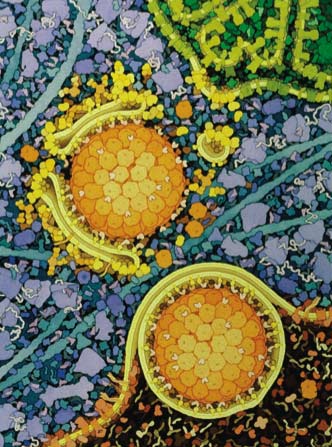

The picture at the top of this post, with the orange spheres, depicts a current model of phagocytosis. It’s a sort of pictorial hypothesis that is incredibly helpful to focus thinking, but – obviously – it’s not true until the structures shown are verified. But is that so obvious? Goodsell’s article also makes the point that

Pictures can be dangerous as well. A clever artist can make even the most preposterous hypothesis seem familiar and plausible. This is doubly difficult with molecular imagery, given that so much of it is computer generated, based more or less on underlying experimental data. Completely believable images can be created for real molecular structures, as well as purely fictional constructs, and unless the sources are reported in the caption, it may be difficult to separate the real ones from the fakes.

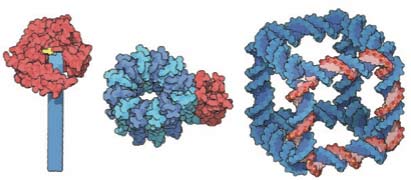

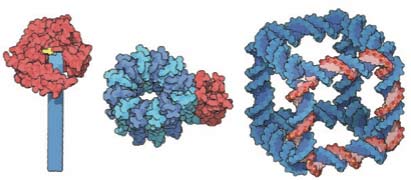

Goodsell offers the following quiz: one of these three molecules is completely imaginary -a fictitious structure for a fictitious molecule. One is based on real structural data, for a real molecule. And one is a fictitious structure for a real molecule. Can you tell the difference?

Obvious? maybe not (I found this article via Biocurious, where the answer, and many guesses, are posted). #3, the DNA cube, is a fictitious structure – but a real (though synthetic) molecule; #1, a nanotube synthase, is the one that’s entirely made up. #2, the rotary motor, is the real structure.

Fiction is a perfectly valid component of art. But fiction in science – once it is known to be fiction – is abhorrent. Scientific/medical art is fascinating precisely because there is powerful tension between the scientific, didactic role of a specimen, supposed to be a purely accurate and objective representation of Nature, and the imaginative realm in which the artist casts it.

Just look at my last post on Delvaux, or indeed, most of the art I’ve discussed on this blog. Even in the simplest botanical print, or inventory of a wonder cabinet, the artist always “frames” the science – it can’t be helped! Choice of medium, choice of angle, choice of context – all of these are choices. The line between representation and story-telling is very fuzzy indeed, and the distinction is hardly science. But then, one shouldn’t expect it to be.

FYI: I couldn’t find the Seed article quoted here online. If you’re interested, it might be worth finding a copy of Seed in your local bookstore – that is, if you’re in a city. You know if YOUR bookstore carries this sort of thing. I couldn’t even find a copy of the New Yorker where I used to live, much less Seed: Science is Culture! If you can’t find a copy, consider subscribing: it’s worth it just for the design.