My excursion in honor of the first ever International Rock-Flipping Day (IRFD), September 2, was disappointing. I was full of hope, given the cicada-filled trees outside my apartment and the bizarre insectoid life I’ve already encountered in the few weeks I’ve been in Washington, DC. But in increasing frustration, I flipped no less than three rocks in the well-watered garden outside my apartment complex, then two more rocks in the dryish park – in desperation, I even flipped a derelict toaster oven!

The only animal I found under any of these objects was one incredibly common pillbug. And I couldn’t even get a decent photo of it before it ran away.

I suppose it could have been worse. After all, the unpretentious, unpoisonous, friendly pillbug is the semi-official mascot of IRFD, depicted on the snazzy badge created by Jason at cephalopodcast:

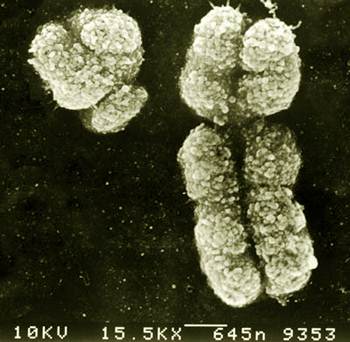

I’ve always loved pillbugs – the glossier and rounder, the better. (I have much less affection for their cousins the sowbugs, because they cannot roll themselves into perfect little balls). Pillbugs were also the occasion for the first great biological discovery of my life. During my childhood rock-flipping phase, I encountered a pillbug brooding its offspring (ghostly white, pin-head-sized versions of their parent). I was mystified; I thought insects simply laid eggs and left them without the slightest regard. So I looked up pillbugs (actually I probably looked up “roly-polies,” because that’s what we called them) and learned they aren’t insects (hexapods) at all. They’re crustaceans. Isopods like sowbugs and pillbugs are closer relations to lobsters and shrimp – even to barnacles – than to anything you’d usually find in your garden, including the very similar millipedes (myriapods). The astonishment of that taxonomic discovery has never left me, and probably went a long way to making me a biologist.

But the wonder doesn’t stop there. As we all know by now, the ocean harbors giant versions of nearly everything – including pillbugs! I wouldn’t care to run into the giant isopod, Bathynomus giganteus:

Deep Sea Giant Isopod – Coda’s flickr stream

or this:

Giant Isopod – NOAA explorer

Why are giant isopods so darn big? I have no clue, but Deep-Sea News took a good try at the question. (You might also ask why terrestrial arthropods are not larger; a recent paper in PNAS identified the oxygen-delivering tracheal system as the limiting factor for certain species of beetle).

Today I was a little disappointed that there were no hexapods or myriapods or arachnids to be seen – not even under the toaster oven. But walking dejectedly back to the apartment with my empty camera, I saw a doe and her still-dappled fawn – definitely too large to have squeezed out from under a rock, but enough to satisfy my frustrated biophilia. Perhaps next year’s IRFD will give more conventional results (mark your calendar now).

In the meantime, check out everyone else’s experiences here: most had much better luck than I did!