I just finished Eric Kandel’s new book, In Search of Memory. For those of you who don’t recognize his name, Kandel won the Nobel Prize in physiology/medicine for his work on the cellular basis of learning and memory. He is also the author, with Tom Jessell and J. H. Schwarz, of the definitive neuroscience textbook, Principles of Neural Science (often called simply “Kandel”). In Search of Memory is part memoir, part popular science, but entirely self-conscious, and it prompted me to think about the way each of us presents ourselves to the world in our writing.

There are two sides to neuroscience: the colorful, anecdote-filled side, and the truly quantitative, equation-filled physiological side. Oliver Sacks, prolific author of The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, etc., pretty much owns the world of anecdotes. He specializes in rare and unique case histories which fascinate and provoke new hypotheses, but can’t lend themselves to rigorous testing. Kandel’s Principles of Neuroscience rests firmly on the other end of the spectrum, on long, repetitive histories of experimentation in unglamorous model systems like flies, snails, worms, and rats. It’s a remarkably useful and comprehensive reference, but I don’t recommend it to any but the hardiest of science undergraduates.

In Search of Memory, like many popular science books, falls somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. It begins with Kandel’s memories of the Holocaust in Vienna; although he and his family escaped to the United States, he uses his childhood disillusionment, confusion, and fear to frame (and justify) his professional quest to understand the human mind. As the book continues, it becomes a history of the nascent field of neuroscience – a lucid history, but one that inevitably revolves around unfamiliar names and places: so-and-so at Columbia, so-and-so at Harvard, etc. Almost all histories of science are recounted in this way, as a litany of names and places. Unless the scientists are made human and interesting, it doesn’t work, and it’s hard to capture personalities without becoming downright gossipy, as James Watson did in The Double Helix.

Kandel conscientiously tags each scientist’s name with a smatter of personality – this colleague played tennis, that one loved symphonies. These details are sometimes perfunctory, and rather disappointingly, the most memorable anecdote about his best female postdoc was apparently that she ran an afternoon daycare in the lab break room! But given the era in which Kandel began as a scientist, he didn’t have many female postdocs, and he always speaks of his female colleagues with respect. Professionally, Kandel gives scrupulous credit to his collaborators: I couldn’t help but notice all the meticulously grammatically correct usages of “_____ and me” or “I and ______”. He also admits his own failings as a father and husband. As he became increasingly embedded in his work, his wife Denise, a professor in her own right, had to take up the slack at home – at the expense of her own career. I’m not sure Kandel regrets this, given the outcome (he especially seems to relish that Nobel Prize ceremony) but at least he acknowledges it.

Upon finishing the book, my overall impression was one of a lively and humane mind, one perhaps more concerned with the minutiae of synaptic transmission than his kids’ school plays – but then, I expect no less from scientists, and Nobel winners at that. The book wasn’t as engrossing as an Oliver Sacks essay, or The Double Helix, but it was interesting, and refreshed my memory of the major turning points in my own field, neurobiology. It would be a good read for a non-scientist who cared about the topic of how neurons work, and was willing to give it reasonable attention. Well-punctuated with personal history, the tale unfolds at a digestible pace. In the end, I felt very favorably toward Kandel, and grateful for yet another popular science book I could recommend to students or friends. That’s when it gets interesting.

Many of my friends are also biologists. When they noticed what I was reading, they all said that Eric Kandel is obnoxious! They said he is the sort of self-important PI who disrespects his subordinates and pits them against each other, as well as many further complaints which, because they are hearsay, I won’t repeat here. One of them had met Kandel briefly and was downright hostile to him; others had heard stories through the everactive science grapevine. What to make of this new evidence? On the one hand, I couldn’t believe that the book I had just read was by the ruthless man they were describing. On the other hand, he had written the book – the framing was his. The winners write the history books, or the science books, as the case may be.

Had I been conned? Is Kandel’s book a self-redaction, a fictitious portrait edited for, and written for, history? I have no idea, because I’ve never worked with or even met Eric Kandel. I can only go with the impression I have from the book, which remains favorable: it’s a good book, written by an intelligent and accomplished man. But I’m disturbed by the failing I’ve detected in myself as a reader: if Kandel were a politician, I’d have opened his memoir with utter cynicism about his motives and reliability. If this were a novel, I’d go in positively gunning for the unreliable narrator. But he’s a fellow scientist! It never occurred to me to question his authenticity or motives. Even objectionable, bigoted scientists are openly objectionable and bigoted (see The Double Helix). Right?

The answer is No, of course not. We all frame our stories, consciously or unconsciously, to reflect those parts of ourselves that we want to share with our readers. I do it here, on this blog: although I believe that my blog “voice” on bioephemera is an extremely accurate reflection of, even insight into, my personality (those of you who know me offline can weigh in on this), it is by no means all of my personality. There are topics I explicitly do not discuss here, and opinions I do not share. Although not as organized as a memoir, each blog post, comment, diary, letter or classroom lecture is an act of editing: facts balanced with message for a specific audience. It may seem obvious, it is obvious, and yet, we too often suspend our skepticism for a trusted source – like a colleague or a friend.

As you probably know, framing science in the political sphere has been a huge controversy all summer. Just yesterday, The Scientist published another article, with editorial commentary, about framing. Should scientists deliberately frame their science? According to one opinion, If you don’t frame it, someone else will. True – if the science is important at all. But I’d argue that no one can avoid framing completely, even if they try; so we shouldn’t try – we should just be open and honest about it.

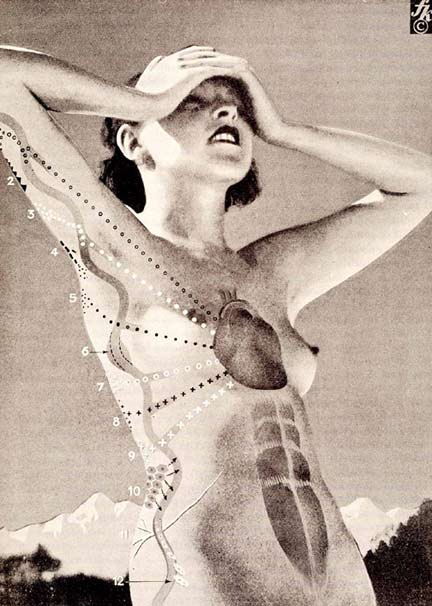

Everything we say and do is molded by our experiences, but perhaps more importantly, by the way we want and need others to see us. We all keep secrets. And it behooves us to remember that scientists are just like everyone else in that respect – fallible. Although the best of us try as hard as humanly possible to be objective, we simply can’t. Any self-aware, truly great scientist will admit this. That’s why science is a group activity: our individual biases will be diluted out and mitigated by our colleagues’. It will all come out in the wash. It’s reassuring to be part of that self-correcting mechanism: whether perfect objectivity is possible or not, we are doing the best we possibly can to be objective. As human beings, with our soft, squishy, fallible brains, we can do no more.

But a memoir is not science. Memory, as any neuroscientist knows well, is far from objective – those squishy brains of ours are idiosyncratic and troublesome, and whatever piquant neural correlates of memory we might find, we will never be able to directly compare our memories to anyone else’s. Eric Kandel laid the foundation for our understanding of how neurons learn, so it’s incredibly fitting that it is his memoir that reminds me today how fallible everything we perceive, learn, and believe can be. Whether he is charming or not, obnoxious or not, this book has been one of the most thought-provoking reads I’ve had in some time.