Microviridae: bacteriophage φX174

Microviridae: bacteriophage φX174

Bugle beads, seed beads, Czech crystals

Holly Wichman

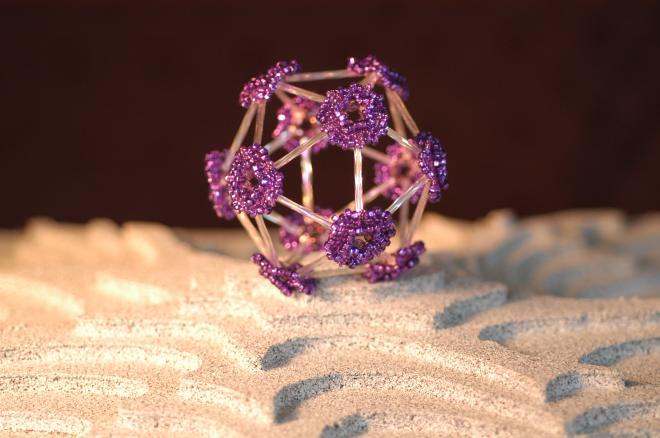

This sculpture made of purple and clear glass beads depicts bacteriophage φX174, a virus that infects bacteria. It rests on a surface that portrays an adaptive landscape, a conceptual visualization. The ridges represent the gene combinations associated with the greatest fitness levels of the virus, as measured by how quickly the virus can reproduce itself. φX174 is an important model system for studies of viral evolution because its genome can readily be sequenced as it evolves under defined laboratory conditions. (source)

The beaded bauble above represents a virus of the family Microviridae – icosahedral bacteriophages, or bacteria-eating viruses. The Microviridae include a bacteriophage that infects and kills Chlamydia, and another bacteriophage that infects Bdellovibrio – itself a parasite preying on other bacteria. Bacteriophages don’t cause disease in humans, and in some cases may even be used therapeutically (for more, see this interesting article in Science).

The artist is Holly Wichman, Professor of Biological Sciences at the University of Idaho. Wichman makes beaded models of the bacteriophages studied in her lab. Wichman infected Bentley Fane, a professor at the University of Arizona, with the beading bug, and the two have collaborated on a collection of beaded virus sculptures.

According to the artists, beading has generated some intuitive insights into viral structure:

When Bentley Fane made his models of structures from T=1 through T = 16, he discovered that some beaded structures were very stable, while others (T = 9, 12, 16) were quite unstable. This is because the sides of the numerous facets directly coinciding with the main edges of the icosahedron. Whether this instability can be extrapolated to viral structures in nature is unknown, but the structures that are unstable when beaded tend to be rare in nature. There is only one known T = 9 particle, and no known T = 12. The T = 16 in nature are the Herpesviruses, and they have both envelopes and teguments to add to stability.

“Crystal Structures: Viruses in Glass” opens tonight at the University of Idaho Reflections Gallery (through October 29, 2007).

Thanks to Jane for the heads up!

For more phage-related art, check out this archive from the 2005 American Society of Microbiology, and this collection, both hosted by Forest Rohwer of SDSU.

2 Responses to Beaded Bacteriophages