ScienceDaily: Why ‘Wanting’ And ‘Liking’ Something Simultaneously Is Overwhelming

“Sometimes a brain will like the rewards it wants. But other times it just wants them.” – Kent Berridge

I once tried to explain to my physiology students that the desire circuit of the brain differs from the pleasure circuit. Not only did I become tongue-tied trying to differentiate between “liking” and “wanting,” I don’t think they believed me. I can’t blame them, because it’s counterintuitive. Why would you want something you don’t enjoy? But a new Journal of Neuroscience article backs me up: wanting something does not necessarily mean you like it.

In daily life, we don’t consistently differentiate between liking, wanting, enjoying, and desiring. We know subtle differences exist, but we tend to ignore them. When I tried to discuss this topic with college freshmen, I think I was doomed from the start – teenagers not only conflate “want” and “like,” they tend to mix in “need” as well! (I remember a few trendy toys I “wanted” desperately, and swore I “needed,” but hardly used, once I had them. The grass is always greener. . .)

On a more serious note, drug addicts don’t necessarily “like” drugs more than non-addicts – they may even find the drugs less enjoyable, if they’ve built up a tolerance to them. But addicts clearly want drugs much more than non-addicts do. Why?

Addiction depends on dopamine, which is often called the “feel-good neurotransmitter” because it mediates pleasurable responses to stimuli like sex, drugs, and food. The addictive potential of a drug is related to how much it increases the pool of extracellular dopamine (meth spikes dopamine levels higher than food, sex, or crack). These dopaminergic pathways are part of the brain’s “reward center” (really, more of a system of circuits than a single center), originally identified in those classic experiments involving rats, electrodes, and levers (and even a few human case studies; see this Damn Interesting post for an overview).

For the past few decades, researchers have attempted to clarify how these pathways generate reward-seeking behavior. At first it seemed dopamine release directly caused the sensation of pleasure. But other evidence suggested dopamine release did not, in itself, cause pleasurable reactions; perhaps dopamine was needed for learning to associate a stimulus with pleasure. The most recent studies, including this one, suggest that dopamine mediates an incentive to seek out the pleasurable stimuli. (Even more confusing, reward pathways may also be involved in aversive responses to negative stimuli – presumably why addictive drugs sometimes cause anxiety, distress, paranoia, etc).

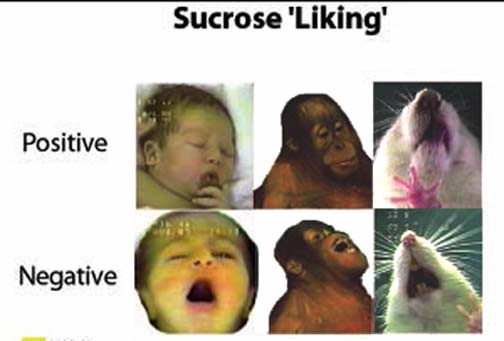

About a decade ago, Kent Berridge suggested that “liking” (pleasure) and “wanting” (incentive) are distinct reward center impulses that can be assessed separately, and that dopamine is primarily involved in “wanting.” To investigate, he exploited the observation that food rewards like sugar elicit typical “liking” behaviors across mammal species. As it turns out, a rat (or ape) noshing on sweets makes appreciative, lip-smacking facial expressions similar to a human baby’s. These indicators are an objective way to assess how much a subject likes a food, independent of how much the subject eats, or the subject’s own subjective impressions of his/her enjoyment.

A human infant, orangutan, and rat display “liking” facial expressions

in response to sucrose, and “disliking” expressions in response to quinine.

Figure from “The Neuroscience of Natural Rewards: Relevance to Addictive Drugs” (2002)

Ann Kelley and Kent Berridge

J Neurosci 22 (9): 3306-3311

In the Journal of Neuroscience study described in this ScienceDaily article, Berridge and Kyle Smith chemically activated a specific “hotspot” in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) of rats. The rats responded in two ways: by “wanting” to eat more food, and by demonstrating more “liking” responses. The researchers then isolated the two behaviors, by activating the NAc while simultaneously inhibiting a different brain area, the ventral pallidum. The rats still ate the increased amount of food, but they no longer showed the extra “liking” responses. Their impulse to eat was motivated by something other than liking the food.

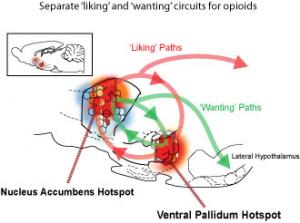

The diagram at the top of this post summarizes the researchers’ hypothesis about the dopaminergic circuits involved. “Wanting” is mediated by an output from the NAc to the hypothalamus, but the “liking” circuit goes through the ventral pallidum, where it can be blocked experimentally. The two impulses are thus independent and separable, even though the same brain centers are common to both. (In previous work, they had shown that directly stimulating the ventral pallidum could modulate both “liking” and “wanting” food, or modulate “wanting” only, depending on the chemical stimulus used).

Unfortunately we don’t know what the rats are thinking. Like a teenager, they may believe they like the food, just because they want it! That sort of rationalization makes it difficult to do human studies on this topic (though some are trying). The obvious relevance of these circuits to addiction and appetite are strong motivations to devise methodologies for human subjects.

I think this kind of research could be particularly important to understanding binge eating – the most common eating disorder in the US, affecting about 3% of the population. In binge eating, the reward system is way off: the hunger drive, the pleasure of eating, and the desire to eat have apparently become decoupled. Not surprisingly, a variant of the dopamine-4 receptor has already been implicated in binge eating, seasonal affective disorder, and winter weight gain.

Binge eaters literally eat until they feel pain: a classic example of how humans can intensely “want” something that we won’t enjoy. The next time you find yourself craving something, ask yourself why, and see if your answer satisfies you. If you won’t really like what you want, you just might rethink what you need.