The words that manufacturers use in product packaging can be a little ambiguous. In an earlier post, I noted that the FDA permits the adjective “light” to be used in reference to the texture or appearance of a food, for example “light and fluffy,” as long as the manufacturer’s meaning is clear. That last bit is included because “light” also can mean “reduced-calorie” or “reduced-fat.” To avoid misleading consumers, Canada allows only this last sense of “light” in packaging, and forbids its use in reference to texture or color.

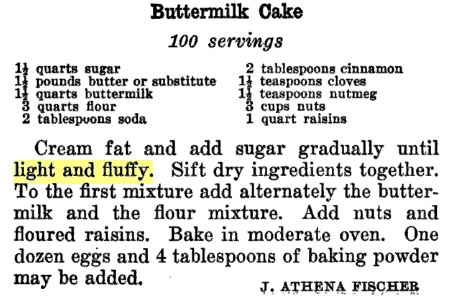

The Canadian regulation seems a bit harsh. After all, qualitative descriptions of “light and fluffy” food easily predate today’s obsession with the calorie. Almost all my mother’s cookie recipes ordain that I “beat until light and fluffy” some unhealthy melange of sugar, butter, and/or eggs. Google Book Search offers up this heart-stoppingly saturated vintage Buttermilk Cake recipe (from the Chicago Dietetic Association’s “Recipes for Institutions”, 1922):

100 servings? Ms. Fischer was efficient.

A consumer can reasonably be expected to understand that, even if “light and fluffy,” Buttermilk Cake batter is not a reduced-calorie food. But other adjectives place an undue burden on the consumer, because they are not clearly defined. Hypoallergenic is arguably the worst of these. Many people aren’t even aware that they don’t know what it means.

Test yourself: which of the following is the best definition of hypoallergenic?

A. does not cause an allergic reaction

B. has a diminished potential for causing an allergic reaction

C. will reduce the number of allergens in the environment of the user

D. contains only extensively hydrolyzed proteins and/or free amino acids

E. fragrance-free

F. safe

The answer is, unfortunately, that it depends on whom you ask. The OED gives (B), but some dictionaries don’t list hypoallergenic at all, because it does not have an unambiguous medical or legal meaning. Like many other scientific-sounding but nebulous words, hypoallergenic was invented for use in mid-century advertising, apparently by combining hypo- (less, below) with allergen. Thus, a hypoallergenic product has reduced allergic potential. But some people may still be allergic to hypoallergenic products, and the severity of their allergic response cannot be predicted. A hypoallergenic product could cause anaphylaxis in a sensitive user. Hypoallergenic does not mean (F) safe.

A substance with no allergenic potential at all, as in definition (A), would be non-allergenic. It is practically impossible to prove that organic products like foods and cosmetics are non-allergenic, because the immune system can potentially recognize millions of molecules as allergens. Some consumer, somewhere, could be allergic to anything. Anti-allergenic products are supposed to reduce other allergens (C). HEPA (High efficiency particulate air) filters are sometimes described as anti-allergenic, as are chemical agents for killing dust mites.

Proteins are potent allergens, which is why the American Academy of Pediatrics decided in 2000 to recommend definition (D) for hypoallergenic infant formula. 2-3% of infants are allergic to cow’s milk formulas, but breaking the allergenic milk proteins down completely (through hydrolysis) renders them unrecognizeable by the infant’s immune system, and threfore safe. The AAP even specifies how the formula should be tested:

These tests should, at a minimum, ensure with 95% confidence that 90% of infants with documented cow’s milk allergy will not react with defined symptoms to the formula under double-blind, placebo-controlled conditions. Such formulas can be labeled hypoallergenic. If the formula being tested is not derived from cow’s milk proteins, the formula must also be evaluated in infants or children with documented allergy to the protein from which the formula was derived. It is also recommended that after a successful double-blind challenge, the clinical testing should include an open challenge using an objective scoring system to document allergic symptoms during a period of 7 days. This is particularly important to detect late-onset reactions to the formula.

In contrast, cosmetics manufacturers may use hypoallergenic to mean (E), fragrance-free, because fragrance ingredients are likely to be irritating when applied to the skin. Many, perhaps most, cosmetics are never tested to determine whether they induce an allergic skin response, because no agency requires them to do so. Each manufacturer is free to decide what they mean by “hypoallergenic,” and their chosen meaning is not vetted by any outside authority. The FDA says quite clearly,

There are no Federal standards or definitions that govern the use of the term “hypoallergenic.” The term means whatever a particular company wants it to mean. Manufacturers of cosmetics labeled as hypoallergenic are not required to submit substantiation of their hypoallergenicity claims to FDA.

The FDA has been aware of the potential confusion here for some time. In 1975, the FDA attempted to clear it up by creating a specific regulatory definition for “hypoallergenic,” which would have required manufacturers to test their products and submit proof that they had a low risk of adverse skin reaction in humans. However, the FDA was challenged in court by Almay and Clinique, two manufacturers who relied heavily on the term “hypoallergenic” in their advertising. The FDA initally won, but in 1977 the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia held the FDA regulation invalid because the FDA had not demonstrated that consumers understood “hypoallergenic” in the way the FDA had defined it. Basically, it seems the FDA attempted to clear up public confusion about the term “hypoallergenic,” but public confusion about the term rendered their effort unenforceable. Puzzling, to say the least!

To give allergy sufferers some measure of protection, the FDA does require that ingredients, including allergenic ingredients, be listed on cosmetic and food packaging. However, the consumer is responsible for checking the label and knowing whether they suffer from an allergy to the ingredients included in the product. (Also, cosmetics labels do not need to specify the individual components of a fragrance – so allergic individuals probably want to choose “fragrance-free” products even if they’re not demonstrably hypoallergenic).

Interestingly, some infant formula manufacturers recently tried to get out of listing milk whey as an ingredient in infant formula, because they claimed it had been so extensively hydrolyzed, it qualified as hypoallergenic (according to the AAP standards). The FDA denied the petition, because the tests conducted by the manufacturer did not prove the product met the AAP requirements for hypoallergenicity. So at least in the case of infant formula, the word does have some regulatory meaning. It’s just hard for the average consumer to know what that meaning is, or when to trust it.

Recently, the word “hypoallergenic” has become attached to a new type of product: cats. I’m planning to write more on this topic later, but Allerca Lifestyle Pets claims to have bred cats which lack the major cat allergen, Feld1. Allerca is now taking orders for hypoallergenic kittens, at $3950 a pop.

Although the supporting data is not yet published, Allerca says that cat-sensitive patients experienced reduced allergic reaction to their hypoallergenic cats, compared with a control cat. If that’s true, it seems fair to call Allerca’s cats hypoallergenic. Anyone who claims “there is no such thing as a hypoallergenic cat” are incorrect. There is no such thing as a non-allergenic cat. But it’s quite possible for a cat to have a reduced potential for allergenicity, compared with other cats.

Several cat breeders cried foul at Allerca’s announcement. They claim that certain cat breeds, including Siberians, Cornish Rexes, and Devon Rexes, are already hypoallergenic (and cheaper). The evidence for this is mostly anecdotal. But since there are no legal or medical standards for using “hypoallergenic” to describe cats, if there is any benefit at all for allergy sufferers to having a Siberian over another cat, Siberian breeders could claim that their cats are hypoallergenic.

At this point, we can’t determine which cats (Allerca’s or Siberians) are more hypoallergenic. No published tests have compared the two breeds of cat. But this is what Allerca claims on their website, in a section entitled “hypoallergenic cats”:

The cat allergen is a potent protein secreted by the cat’s skin and salivary glands. ALLERCA has focused on naturally occurring genetic divergences (GD) already present in cats that do no harm to the cats in any way. The resulting ALLERCA GD hypoallergenic cats will now improve the health and quality of life for millions of cat-allergy sufferers.

While some breeds of cats have been promoted as having less allergen than others, scientists that have tested this hypothesis have shown that all cats, regardless of breed, produce allergens. The ALLERCA GD cat is the only scientifically-proven cat that helps those individuals with feline allergies and was developed using proprietary methods under ALLERCA’s pending patents.

Hold on there! Even if the Allerca cats completely lack the allergenic glycoprotein Feld1, which they have not proven, the Allerca cats would still have other potential protein allergens. There is not, and cannot be, a non-allergenic cat. But that doesn’t invalidate the proposition that some breeds of cat “have less allergen than others.” Given the genetic variation between individual cats, it seems quite possible that some would produce less Feld1. In fact, Allerca claims they created their hypoallergenic cats by screening for animals with a naturally occurring “genetic divergence” in the Feld1 gene. Allerca’s statement is technically correct, but misleading, insofar as it implies that Allerca is the only source of cats with reduced allergic potential. Allerca has not yet proven that Siberian cats aren’t just as hypoallergenic as the Allerca cat. Show me the data, Allerca.

The bottom line: be skeptical of the word “hypoallergenic.” It does not mean “safe,” and the person using it is usually trying to sell you something expensive.

And while you’re at it, you might want to stay away from that Buttermilk Cake too. You might not be allergic to it, but that doesn’t mean it’s good for you.

3 Responses to Beat until light, fluffy, and hypoallergenic