from xkcd.com

A few months ago, I dreamed that I attended a cocktail party, where I mistook Simon Baron-Cohen (the neurobiologist) for his cousin Sacha Baron Cohen (better known as Borat). I don’t know why either of them was in my dream (I haven’t even seen Borat), but if the opportunity ever comes up, I would like to pick the neurobiologist’s brain over cocktails. I don’t know quite what to think about his suggestion that autism might be caused by assortative mating among technogeeks – not to mention the bit about men and women having differently abled brains.

Autism is getting more and more attention, both in the media and in research. But we still don’t understand the developmental causes of autism. We don’t know how to define what has gone awry in autistic children, much less fix it. This confusion has fueled a rash of hypotheses (and lawsuits) over possible causes – most of which are unsupported by scientific evidence. But parents want some explanation: as many as 1 in 100 of their children will be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Whether there is a new autism “epidemic,” or we’re just catching cases that twenty years ago would have gone undiagnosed, is still unclear.

For the past several years, Baron-Cohen and his collaborators have been fleshing out a genetic model for autism. Twin studies support the idea that autism is genetic – the best predictor for autism is a twin with autism. But why do children of non-autistic parents become autistic? And why is the rate of autism increasing? Unlike more straightforward genetic conditions such as Tay-Sachs or hemophilia, where a “bad” allele of a gene causes a well-defined disease, autism probably involves multiple genes with additive effects – alleles that are benign, even beneficial, in normal individuals, could contribute to autism in the right (or wrong) combinations.

As summarized in this 2003 Guardian article, Baron-Cohen maps autism along the same continuum as gender differences in cognition. So let’s start with that. According to his model, women tend to be “empathizing,” while men are more “systematizing”:

Systemizing involves identifying the laws that govern how a system works. Once you know the laws, you can control the system or predict its behavior. Empathizing, on the other hand, involves recognizing what another person may be feeling or thinking, and responding to those feelings with an appropriate emotion of one’s own. (“The Systematizing Brain,” NYT, 2005)

This is, of course, a simplification – individual men and women could fall anywhere on the E-S continuum; most of us are a middling balance of E and S. But the idea is that, in bulk, most men tend to be S while most women are E.

Such claims about gender differences in mental processing are understandably controversial, especially when they reinforce cultural stereotypes. Baron-Cohen’s papers are peppered with phrases like “typical male interests (e.g., in mechanics)”. He knows he’s treading dangerous ground, and isn’t shy about it:

Two big scientific debates have attracted a lot of attention over the past year. One concerns the causes of autism, while the other addresses differences in scientific aptitude between the sexes. At the risk of adding fuel to both fires, I submit that these two lines of inquiry have a great deal in common. (“The Systematizing Brain”, NYT, 2005)

I’m not going to get into that gender-bias mudhole. But just to balance things out, here’s a typical response from his critics.

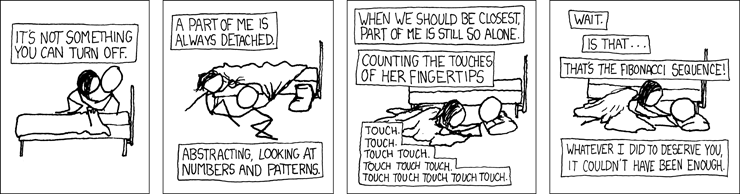

Anyway, within the E (female) – S (male) spectrum, Baron-Cohen characterizes autism as a hyper-systematizing brain (an extremely male brain). When S dominates E, the ability to form interpersonal relationships and communicate with others could be hindered. If you’d like to get a feeling for how “systematizing” you are, Baron-Cohen’s autism quotient (AQ) test (Wired) is a blunt-force gauge of autistic traits for adults. The relevant research paper is linked at the bottom of this post; the average AQ test score is supposed to be 16-17. The automatic scoring at Wired wasn’t working when I checked, but the test is also mirrored here at OK Cupid, so try there first.

Although the AQ test emphatically CANNOT diagnose autism, autistic individuals tend to have scores over 32. And as you’d expect from the previous paragraphs, AQ is also correlated with gender: men usually score higher than women do.

EQSQ also has a little systematizing/empathizing quiz: I have no idea if this one’s based on science at all, but it tries to assess if you are more S or E.

If you’d like more detail on why brains are either empathizing or systematizing, you should read this article from Entelechy, “The Biology of Imagination.” In it, Baron-Cohen hypothesizes that developmental deficits in certain brain circuits might impair the acquisition of empathy, shifting the balance toward systematizing. The general idea is that humans (and cats, dogs, etc.) can easily generate primary mental representations of the world around them. But it’s harder to handle “second-order” representations, like the imagined perspectives and feelings of other people:

Let’s define mind-reading as the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes, to imagine the other person’s thoughts and feelings. . .

To mind-read, or to imagine the world from someone else’s different perspective, one has to switch from one’s own primary representations (what one takes to be true of the world) to someone else’s representation (what they take to be true of the world, even if this could be untrue). Arguably, empathy, dialogue, and relationships are all impossible without such an ability to switch between our primary and our second-order representations. (Entelechy)

Baron-Cohen suggests that genetic influences on the growing brain could specifically affect the development of this capability:

In the vast majority of the population, this module functions well. It can be seen in the normal infant at 14 months old who can introduce pretence into their play; seen in the normal 4 year old child who can employ mind-reading in their relationships and thus appreciate different points of view; or seen in the adult novelist who can imagine all sorts of scenarios that exist nowhere except in her own imagination, and in the imagination of her reader.

But sometimes this module can fail to develop in the normal way. A child might be delayed in developing this special piece of hardware: meta-representation. The consequence would be that they find it hard to mind-read others. This appears to be the case in children with Asperger Syndrome. They have degrees of difficulty with mind-reading. Or they may never develop meta-representation, such that they are effectively ‘mind-blind’. This appears to be the case in children with severe or extreme (classic) autism. Given that classic autism and Asperger Syndrome are both sub-groups on what is today recognized as the ‘autistic spectrum’, and that this spectrum appears to be caused by genetic factors affecting brain development, the inference from this is that the capacity for meta-representation itself may depend on genes that can build the relevant brain structures, that allow us to imagine other people’s worlds. (Entelechy)

If each person has some alleles pushing the developing brain towards E, and other alleles pushing toward S, then an imbalance of those normally harmless alleles could cause a brain to become excessively S. How would such a genetic imbalance arise? As in this article from last November’s Seed, Baron-Cohen suggests that assortative mating – strongly systematizing men preferentially choosing systematizing women, or vice versa – could, through basic genetic principles, produce even more systematizing offspring. It’s as simple as a tall couple getting together and having even taller children. And Baron-Cohen has data to support it:

First, both parents of children with autism are likely to be super-fast on attention tasks, in which the aim is to spot a detail as quickly as possible. Second, both parents have an increased likelihood of having had a father who worked in the field of engineering. Third, both parents are more likely to have elevated scores on subtle measures of autistic traits. And fourth, both parents show a trend toward a more male pattern of brain activity when measured using MRI.

The chances of both parents displaying these similarities are vanishingly small. Something must be causing two such individuals to be attracted to one another. I propose that “something” is strong systematizing—the drive to analyze the details of a system in order to understand how it works. (Seed)

Parents of autistic children score higher on the AQ test than other parents – indicating that, while not themselves autistic, they have systematizing tendencies. The higher the AQ score, the stronger those tendencies are. Scientists and engineers (both male and female) tend to score higher on the AQ test than non-scientists. (Remember, systematizing is only a detriment if taken to extremes; most of us would like to be better at pattern recognition and analysis.)

If systematizers are marrying each other in increasing numbers, and bearing increasingly systematizing children, could it explain a suspicious increase in autism in, of all places, Silicon Valley? Hmmmm.

On the AQ test, I scored a measly 20. I guess from a genetic standpoint, it would be safe for me to reproduce with an engineer, or another scientist. But on the other hand, biologists have the lowest average AQ out of several scientific disciplines tested – my score is actually high for a biologist. Even worse, according to EQSQ.com, I’m a Y-chromosome level systematizer! I’m supposedly less empathetic than the average man – which will no doubt disconcert everybody who has seen me practically burst into tears over a “sad” inanimate object, like the IKEA lamp. (it’s all alone! in the rain!)

Maybe I do have a few autistic personality quirks. But I also have a few stereotypically “male” mental tendencies, like a talent for reading maps and mentally rotating objects. I’m obviously not male. Nor am I autistic. (And I think EQSQ’s test claims I’m a systematizer because I’m rabidly curious – not because I’m systematic about my curiosity). Where exactly should we draw the line between personality quirks and symptoms? What does something like the AQ test really indicate? There seems to be some hypothetical tipping point, at which a geeky personality morphs into autistic pathology, and I have difficulty with that. Which is probably why I’m a biologist, not a psychologist.

Diagnosing Asperger syndrome (AS) is especially problematic. AS is a high-functioning autism spectrum disorder, in which IQ is not compromised. But experts can’t agree on whether AS is a mild form of autism, or a related disorder. One of my professors fit the AS stereotype perfectly: brilliant, observant, obsessed with details, completely oblivious to interpersonal problems, and utterly lacking in empathy. I’d say he was illogical about people – an adjective that would never apply to his meticulous research. Did he have autism/Asperger syndrome? Or was he just a preoccupied geek with atrocious managerial skills?

What about an obsessively organized polymath like Thomas Jefferson – did he also have AS, as Norm Ledgin claims in Diagnosing Jefferson? Or was he just an eccentric genius? Baron-Cohen and his collaborator Ioan James have suggested that science’s most revered figures, Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein, were autistic. But not everyone buys it:

Glen Elliott, a psychiatrist from the University of California at San Francisco, is not convinced. He says attempting to diagnose on the basis of biographical information is extremely unreliable, and points out that any behaviour can have various causes. He thinks being highly intelligent would itself have shaped Newton and Einstein’s personalities.

“One can imagine geniuses who are socially inept and yet not remotely autistic,” he says. “Impatience with the intellectual slowness of others, narcissism and passion for one’s mission in life might combine to make such an individuals isolative and difficult.” Elliott adds that Einstein had a good sense of humour, a trait that is virtually unknown in people with severe Asperger syndrome. (New Scientist)

Narcissistic, isolative, difficult, wicked sense of humor, impatient with the intellectual slowness of others. . .sounds perfect!

Speaking of fictional characters, even prickly Mr. Darcy from Pride and Prejudice has been labeled autistic, in which case autistic tendencies are catnip to tens of thousands of Darcy-loving females across America. I’m somehow skeptical.

However flawed the book’s historical premise, the Amazon reviews of Diagnosing Jefferson include some glowing, grateful comments from the parents of children with autism. These parents want to believe that their children can and will be successful (after all, if a father of our nation was autistic. . . ). Baron-Cohen seems to share their concern; he constantly emphasizes the unique perspective and gifts of autistic/AS children. It’s true that a few articulate, successful autistics, like animal behaviorist Temple Grandin, do gain unique insights from their condition. If I ever teach neurobiology again, Oliver Sacks’ essay-portrait of Dr. Grandin, titled “An Anthropologist on Mars” (Grandin’s own phrase) will be required reading. It’s a wonderful lesson in forming those second-order representations, trying to imagine an autistic individual’s perspective on the world.

Yet the diagnosis of autism is almost always a stunning tragedy for affected families. And if Baron-Cohen’s assortative mating hypothesis is correct, and autism is caused by concentrating otherwise neutral, even advantageous, “systematizing” alleles – how can we possibly prevent autism? We can’t prohibit extreme systematizers from marrying because they might have autistic children. There’s no meaningful way to measure that risk in advance, as there is for single-gene disorders. How do we combat a “disease” that’s the unpredictable product of completely normal human genetic variability? I don’t have an answer for that, and I don’t think anyone does.

Additional resources: Simon Baron-Cohen, “The hyper-systematizing, assortative mating theory of autism” (pdf)

Simon Baron-Cohen, et. al., “The Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ)” (pdf)

Pingback: Do you have an engineer in the family?

Pingback: My Biotech Life » Gene Genie #12 aka The Dozen

Pingback: bioephemera.com » A Different Kind of Asperger's