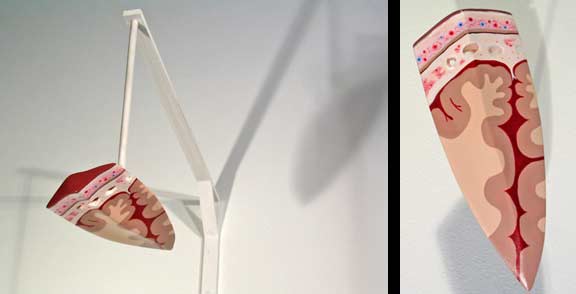

Iliad Cenotaphs: Echepolus

acrylic on wood

Jonathan Gabel, 2007

Poring over the hyper-detailed text of the Iliad, Jonathan Gabel has envisioned each soldier’s death-wound, recreating the negative space of the wound as an anatomical model.

The result is striking: each model represents a tiny fraction of the human body, but a part essential to its integrity as a whole. The wound that killed Echepolus, above, was a direct hit to the front of the skull:

Antilochus was the first to kill a man—

a well-armed Trojan warrior, Echepolus,

son of Thalysius, a courageous man,

who fought in the front ranks. He hit his helmet crest,

topped with horsehair plumes, spearing his forehead.

The bronze point smashed straight through the frontal bone.

Darkness hid his eyes and he collapsed, like a tower,

falling down into that frenzied battle.

The model is shaped like a speartip, as if it had been cast directly from Echepolus’ gaping wound. Spongy white frontal bone and the wiggly profile of the cerebral cortex are clearly visible. Each of the five pieces in the series match Homer’s account: the slightly larger track of Democoon’s temporal deathblow transects his eyes and nasal sinuses; unfortunate Leucus got it in the groin. . . Gabel appears to proceed chronologically; if he intends to finish the Iliad, he has a couple hundred more soldiers to go.

Such careful reconstruction of the medical details of an epic battle may make Gabel the classical equivalent of a rabidly picky fanboy. But it’s also an effective way to shift the romanticized, rhyme-encrusted deaths of literary heroes into a less glorified space: the ER. Films like the 300 make ancient war look like a dance. But war, in any time and place, involves chopping people into meaty, exposed chunks. It’s appropriate to be reminded of that.

*****

As I was putting this post together, the Proceedings of the Athanasius Kircher Society called my attention to another remarkable instance of the body as negative space: the plaster casts of Pompeii. In 79 AD, Pompeii and its twenty thousand inhabitants were buried by toxic gases and ash from the eruption of nearby Vesuvius. The hot ash hardened, and as the corpses of its victims decayed, they left body-shaped hollow cavities in the ash.

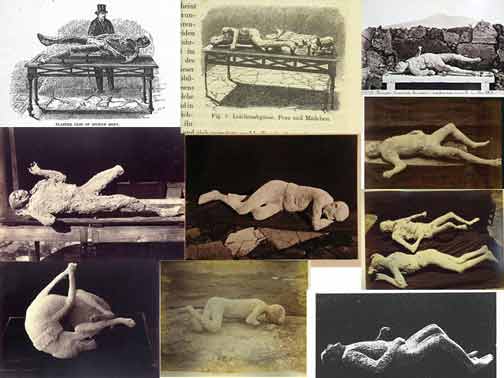

Composite image of the first twelve body casts from Pompeii

from “From Fragments to Icons” by Eugene Dwyer, Interpreting Ceramics 2005

Beginning in 1863, the agonized forms of Pompeii’s dead were recaptured, as a series of plaster casts made from these negative spaces (the ash “molds” were destroyed in the process). Some casts are detailed enough to capture contorted faces and folds of clothing. In the 1980s, a translucent resin-epoxy material was tried that would not conceal any bones or other objects still in the cavity, resulting in a gruesome wax-like representation of a young girl, her teeth and bones exposed to view.

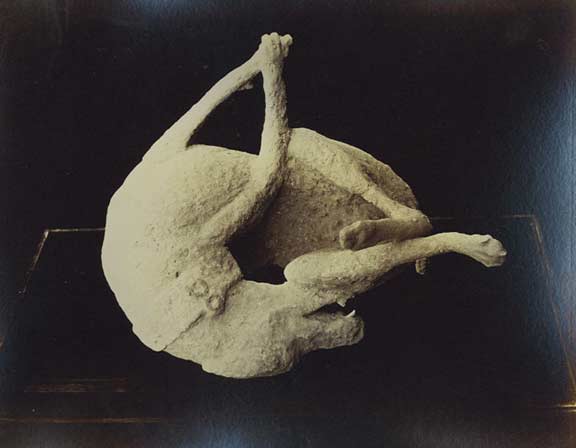

But most poignant are the nearly featureless casts, almost cartoon-like, in which the position and angles of the body are more than sufficient to convey signify terror or resignation. The suprisingly graceful cast of a desperately writhing dog, unable to escape its chain, is perhaps as close as art can get to capturing death without a trace of self-consciousness.

Watchdog (“chained dog”)

plaster cast, 1874

photo: G. Sommer

from “From Fragments to Icons” by Eugene Dwyer, Interpreting Ceramics 2005

Certainly interesting. There is in fact, poetry in the dog’s contorted, almost impossible posture!