Image source: UNESCO (visit site for higher-res image)

This week, Patent Baristas have an excellent (as usual) post on Abbott Labs’ ongoing conflict with the government of Thailand. This unfortunate situation illustrates some key difficulties in getting expensive pharmaceuticals to impoverished populations. It’s tough when public health and free enterprise collide – it sometimes makes me glad that I’m just a biologist.

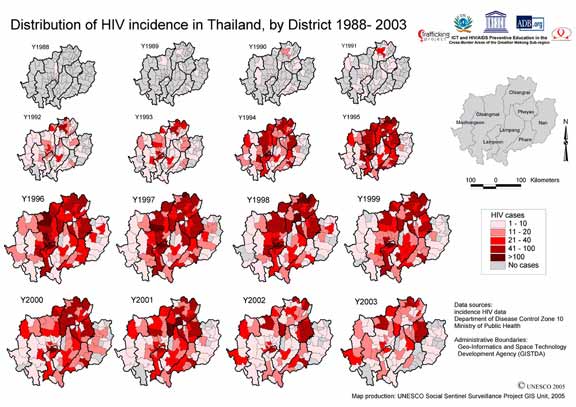

Over half a million Thai citizens are HIV-positive – in a country of 65 million, that’s about 1 in 100. The Thai government supplies about 80,000 AIDS patients with subsidized anti-retroviral drugs, including Abbott’s Kaletra. The problem is that the Thai government doesn’t want to pay full price for Kaletra to Abbott. So Thailand issued a compulsory license in January, allowing them to buy a generic version of Kaletra, probably to come from an Indian manufacturer.

A generic manufacturer will sell Kaletra to the Thai government more cheaply than Abbott will – partly because Abbott bears the original cost of research and development on the drug (as well as its ill-fated cousins – most drugs that undergo R&D don’t make it, and the company must recoup the costs of those failed drugs somewhere). The Thai government will save money (about $24 million a year); Abbott, on the other hand, will lose the Thai market – and because it’s difficult to prevent shipments of generic drugs from illicitly entering the global market, Abbott may lose sales of Kaletra in markets outside Thailand as well.

Was Abbott shamelessly exploiting the Thai AIDS patients for profit? Not exactly. Abbott was already giving Thailand a discount, selling a year’s worth of Kaletra to Thai patients for $2,200, most of which cost, I understand, is borne by the Thai government. The generic version will cost about half that. US patients, in contrast, get Kaletra for about $7,000 a year, and because the US respects Abbot’s patent, no generic is available here.

It smarts that an AIDS patient might have a better chance of affording retrovirals in Thailand than in the US. On the other hand, the recent Thai HIV infection rate is a national health crisis. Over the past decades, Thailand has instituted a number of efforts to slow infections down, including compulsory condom use among sex workers, advertising and education, blood testing, etc. This worked quite well for a few years, but efforts have fallen off. A Thai health minister has promised that the money saved on Kaletra would be used to fund even more AIDS prevention measures (reference). Thailand is simply trying to get the most anti-AIDS bang for its buck. And according to international law, the compulsory patent was totally legal.

Abbott, on the other hand, has a duty to its shareholders to avoid losing money. So the company decided not to bring any new drugs to Thailand at all, and rescinded seven drug applications it had already made. Health activists are crying foul, but Abbot is behaving rationally: if it’s not going to make money in a market because its patents won’t be respected, why invest there? Unfortunately, that means Thai patients will lose access to at least seven new Abbott drugs, in exchange for a better price on a drug that was already available. For the individual Thai patient, that may turn out to be a good deal, or it may not. This is really a no-win, frustrating situation.

I guess this example shows why it was foul play in the first place to leave most of pharmacological research to the private industry. A private industry which, in spite of its outrageously high rate of return on investment (among the top ones in all industry), is also indirectly subsidized by taxpayers through public medical research. I really doubt that Abbott will desert the 65-million people Thai market for long. So the situation may end up as a win-lose one (for Thailand, that is, not for Abbott’s shareholders obviously).

was the “more bang for the buck” pun intentional?

I grant that many pharma companies benefit from public research but Pierre, you can’t seriously be arguing that we would have a comparable selection of drugs available to the world without private research firms.

I’m torn regarding pharmaceutical companies partly because of the humanity vs. profit dilemma, but also because it’s it’s only health care in the most superficial sense of taking a pill to solve an immediate problem instead of actually living in a healthy manner. No matter my misgivings though, I can’t deny the good they do for people.

Ph, and regarding Thai land, have you read “Bangkok 8”? It’s a fantastic novel set in thailand. Really captures the flavor of the country, from it’s spiritual subtleties to its attitudes concerning sex, corruption and the western mentailty. A truly fantastic read.

Yes, the “more bang for the buck” line made me wonder too. 🙂

Thank you for the reading advice. I never heard about that book, I will try to look for it.

Now, about your response:

“I grant that many pharma companies benefit from public research but Pierre, you can’t seriously be arguing that we would have a comparable selection of drugs available to the world without private research firms.”

And why not ? I mean, cite me a single technological breakthrough in the XXth century that was NOT primarily based on public research ? I have not a single example in mind, from the transistor to the laser or the internet.

Do not get me wrong: private-funded research (or what is left of it in today’s financial economy) has always advanced hand in hand with the public sector, tackling issues with a different (and often complementary) perspective. As a researcher myself, my work has often benefited from such partnership. So I am not claiming that pharmaceutical research should all be made in public institutions. Only private companies will be able, indeed, to include a real cost-effectiveness assesment of processes or marketing policies, things that are obviously not within the grasp of public researchers.

But the “humanity vs profit dilemma”, as you put it, tends to suggest that the issue of public health is doomed if left entirely to the private sector. When it comes to dealing with drug companies, it is clear that only governments, and definitely not private insurance companies (let alone individuals), may have enough power to negociate a fair trade. So the action of the Thai government is, in a way, just part of a tough negociation process. It is a move which may stimulate other similar reactions from developping countries (as happened before on the same issue, in South Africa for instance), at which point the sheer size of the involved market will force pharmaceutical companies to reconsider their commercial policies. Could such a balance of force be achieved without the intervention of governments ? I do not think so.

Regards,

Pierre

Oh, you two. 🙂 No, I didn’t mean the “bang for the buck” comment! But I’m not surprised I said it – my subconscious, or my subordinate hemisphere, or some part of my brain, has a habit of making very bad puns which no one believes are inadvertant, and that I don’t notice until they’re pointed out to me. Sigh.

Haven’t read Bangkok 8. Will add to interminable to-read list.

As for the topic at hand, I was careful in this post not to push it too much one direction or the other. . . I’m kind of on both sides at once. I saw an excellent panel discussion on this issue last week, and I have a post in the works about it, but who knows when I’ll get it finished – the time issue again. I’ll try to fast-track it though because it deals with the very public/private issues you’ve raised, and it would be better to have as a post than as a comment.

Thank you for taking the time to drop by in spite of your present work load. I will be impatient to read your post about the issue we discussed here.

Best,

Pierre

The first commenter was dead on…

“A private industry which, in spite of its outrageously high rate of return on investment (among the top ones in all industry), is also indirectly subsidized by taxpayers through public medical research.”

And don’t forget what Chris Rock said about Big Pharma (I’m paraphrasing)… “Drug companies don’t want to cure diseases, they just want to treat them. Think about how many dollars were lost with the polio vaccine.”

Not surprisingly, the polio vaccine came from non-profit institutions. Keep in mind that the overriding goal of any for-profit corporation is to make money, even paramount to saving lives.

Think of it this way.. How long do you think it took Abbott to recoup their investment on R&D? A year? One shipment? Keep in mind the R&D was helped along by tax breaks, etc. You might want to consult “The Truth About Drug Companies” written by a former medical journal editor, Marcia Angell.

This is a very interesting website, I too am a researcher and am interested in many of the concepts here.

Thanks,

Drew

Drew – the question is not “does public research money contribute to drugs sold for profit.” of course it has, and does, and will. Drug companies absolutely benefit from public research. Duh.

The problem is that people seem to expect this public investment to make for-profit companies like Abbott act altruistically. Why would they? One of the reasons so much public money goes into easing a potential drug toward a commercializable point is that drug companies will not willingly lose money. If we want a drug rapidly commercialized and widely available, the best way to do it in the current system is to make it a clearly profitable bet for a drug company. Whether you think Abbott’s profit is commensurate with their effort, whether profit is even appropriate given the public research investment – none of that is relevant. What matters is whether Abbott or some other company thinks they will make enough money off the drug to make it worth their trouble. Because if they won’t, then a public entity or a nonprofit entity would have to bring it to market. Which might or might not happen.

A similar problem exists for the science journals. Whether you think it’s fair that you, a member of the public, have to pay twice for research – once in funding the research, then second, to subscribe to a journal and read about it – is really not the question. It doesn’t matter if you think Nature or Science make too much money. The question is if journals become insufficiently profitable, how will the peer review model and dissemination of research be funded? Again, the private for-profit system is what we have now. It’s changing, but it’s taking years, and it’s still unclear how it will work out. And there’s a lot less money at stake in publishing than in drugs.