Language Log: Foolish Hobgoblins

It’s been many long years since I was an English major. That’s my standard justification when I get sloppy and split some infinitives, or use “which” when I ought to write “that.” I put punctuation inside and outside of quotation marks as it suits me, and use British spellings on a whim. As long as my meaning is clear, and it doesn’t violate my aesthetic sense, I just don’t feel strongly about consistency. This Language Log post summarizes my attitudes pretty well. It’s a relief to hear from such a qualified source that I’m not completely alone in my negligence.

I’ve wondered if some of my linguistic laxity derives from my science training – not only through lack of writing practice, but through an elevated tolerance for uncertainty. In science, there is no conclusively “right” answer. You always consider several possible models, and although eventually experimentation narrows these possibilities down, in the meantime you must respect them all. In short, in the absence of good evidence, you shouldn’t arbitrarily prioritize one hypothesis over another. I feel the same way about language. When the meaning is plain, and several alternatives are used by equally good writers (whether from different historical periods, different countries, or different academic cultures – the Language Log post gives a number of good examples) I don’t feel there’s good reason to prioritize one usage over another.

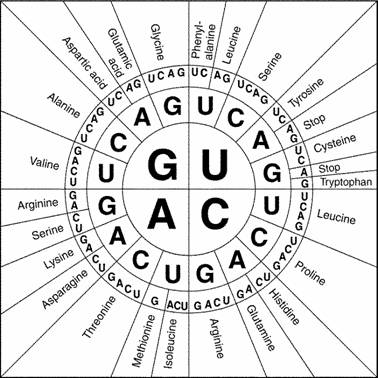

In genetics, you learn to look past variation that isn’t relevant to the issue under investigation. Every gene exists in multiple versions, or alleles, but only some of those alleles have significantly altered functions. The rest are pretty much equivalent. The RNA codons GCA and GCG both encode alanine, so I don’t particularly care which is used in a gene, because I get the same protein either way. It’s like a regional variation in pronunciation: if we all understand what’s meant, why nitpick?

![codon[1].gif](http://bioephemera.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/03/codon%5B1%5D.gif)

Two representations of the RNA codon table. Sources: (1), (2)

When discussing equivalent codons, I dislike the adjective “degenerate.” I prefer “redundant” because “degenerate” has negative connotations (an example) that can mislead students. Reserving several ways to encode a given amino acid does not make the genetic code less effective or elegant – in many ways, it makes the code more robust. Moving up a level, genetic diversity is the basis for evolution, and for the health and stability of ecosystems. When you see subtle variation as beauty and bounty, it’s harder to arbitrarily winnow it out – even in the names of Strunk & White.

Of course, not all variations are equally optimal in all contexts. Sometimes, there are valid, utilitarian reasons to prefer one usage over another. Different species tend to prefer different codons for certain amino acids and express those codons more efficiently – a significant concern for genetic engineers who are “transplanting” genes from one organism into another. A cloned gene may be less effective in its new host, if the host has different codon preferences; some tweaking to match those preferences may be required to optimize the gene’s performance. In this case, the preference for one codon over another isn’t arbitrary – it improves the gene’s function in its new context. Anyone who has submitted an article to multiple journals, and had to reformat the citations each time to meet each journal’s unique specifications, knows exactly how this process works.

Codon preference was part of a long-running patent dispute between several biotech companies, including Monsanto and Dow, whose researchers used the Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) toxin gene to create pest-resistant corn and cotton crops. Optimizing Bt toxin production in the new host plants required tweaking the cloned Bt gene to match the host’s preferences. Like the construction “y’all” – melodious in a Louisiana accent, but not so pleasant in a Boston accent – the Bt toxin allele native to Bacillus wasn’t the best choice for cotton, a dicot plant. The Bt gene had to be edited so it would read fluently in a “dicot accent.” (The patent dispute focused on the methodology used to do this. Among other issues, the meaning of the phrase “codon preference” was disputed. See a summary of the long-running dispute here. Patent writing, like genetic engineering, has tighter linguistic constraints than blogging, and little tolerance for inconsistency).

The bacterial Bt allele wasn’t the best choice for a dicot plant like cotton, but it still worked. Similarly, when choosing among variants of spelling, pronunciation, or phrasing, different writers may make different choices because more than one variant works. If one variant is sometimes more effective than the others, that actually argues against enforcing consistency, because the best choice will depend on context. That’s why many black-and-white rules intended to enforce consistency, like Conservapedia’s insistence on Americanized spellings, seem silly to me. Is consistency really that big a virtue? If so, I’m an unrepentant sinner. And Conservapedia will no doubt agree.

PS. I was pleasantly surprised to see as I posted this today that two books about the consistency issue are reviewed in today’s NYT, one by Ben Yagoda:

His book, an ode to the parts of speech, isn’t about the rights or wrongs of English. It’s about the wonder of it all: the beauty, the joy, the fun of a language enriched by poets like Lily Tomlin, Fats Waller and Dizzy Dean (to whom we owe “slud,†as in “Rizzuto slud into secondâ€).

and one by David Crystal:

When he’s not being cranky, Crystal is fascinating and insightful, often funny. He’s especially good on the Middle Ages. When printing came to Britain in 1400, English was a merry old mess. Choices had to be made, he says, and typesetters were often the ones making them. “If a line of type was a bit short on the page, well, just add an -e to a few words.†And if it was too long? Just “take out some e’s.â€

More books for my Amazon Wishlist!

First year Biology students at the U of A have to write 2 essays, each with a 500 word limit. They have a hard time with this. I’ve seen some really good essays that would lose marks based on excessive wordiness. I’ve seen others that are under the limit, but lacking content. But balancing meaning with brevity might well be the most useful skill you can learn as an undergrad science student. Granting agencies, journals, and abstracts all reinforce meaning over style in scientific writing by imposing Draconian word limits. In the same way that the old typesetters eliminated letters to suit their needs, so to does the scientist remove grammar to slip in under the word limit.

Pingback: Caveat lector « Sciencesque

Ha. I’ve written four or five length-restricted essays and memos in the past three months, and found myself making all sorts of questionable grammatical elisions! Your point brings up another parallel with biology: fast-reproducing organisms like bacteria must have tightly edited genetic code, like an abstract or brief, while humans can get away with all kinds of wordiness and useless junk in our DNA. Our genome is like the tax code.

Hello- glad to have found your blog. I enjoy the words and the visual aspect as well (odd perhaps, but those things seem to matter to me as well). As a biology teacher, I found the following simple little paragraph to hold a really nice summary that will help me explain a sliver of fact in my class:

“In genetics, you learn to look past variation that isn’t relevant to the issue under investigation. Every gene exists in multiple versions, or alleles, but only some of those alleles have significantly altered functions. The rest are pretty much equivalent. The RNA codons GCA and GCG both encode alanine, so I don’t particularly care which is used in a gene, because I get the same protein either way. It’s like a regional variation in pronunciation: if we all understand what’s meant, why nitpick?”

That is one of the “tiny little things” that plays out in a much larger way in biology and in life.

Like I said- glad to have found your little home on web. I’m sure I’ll stop back by from time to time.

Thanks much,

Sean