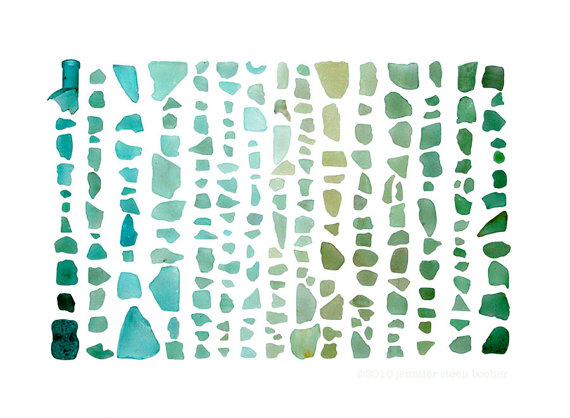

Seaglass Spectrum: Aquamarine to Emerald

Jennifer Steen Booher

Assemblage artist and photographer Jennifer Steen Booher collects, arranges, and photographs found objects. Â Her arrays of beach glass resemble abstract art, or pages from illustrated catalogs of Renaissance wonder cabinets, while household junk becomes almost archaeological.

While each patinated object alone might be worth a long gaze, it is Jennifer’s unerring sense of space and color that turns her collections into cohesive forms that work as photographs. Â The white space between the objects is not merely emptiness or blank cotton in a drawer, but interactive and essential — the mortar of a mosaic, or the paper in Scissors, Paper, Stone:

Scissors, Paper, Stone

8×8 print

Jennifer Steen Booher

Jennifer’s work resembles a wonder cabinet.  Unsurprisingly, her Maine studio sounds like it is a wonder cabinet:

My studio is lined with shelves, and the shelves are lined with boxes. The boxes have labels like “Bones,” “Alphabets,” “Numbers,” and “Animals.” These bits are from the box labelled “Clocks.” [describing “Time Pieces“].

If I had more time and space (an art studio!), that is exactly what I’d do: accumulate boxes of found objects and wait for inspiration. (According to my fiance, I do this already).  I’ve collected many things over the years; blue glass Ball jars, geodes, Fisher-Price wooden people — but Jennifer has me beat; I don’t have a studio brimming with boxes of objects, and I don’t have twenty toy fire trucks. So jealous.

If you believe all those decorating blogs and magazines, collecting and displaying found objects is something we all do, but it is something best done by cosmopolitan designers and the proprietors of exclusive boutiques.  Sibella Court’s Anthropologie-esque book The Life of a Bowerbird: Creating Beautiful Interiors with the Things You Collect, is a charming paean to found and upcycled objects, with sections on safety pins and homespun.  But her style is also a little . . . rarefied.  Her chapter on beachcombing, which is delightfully titled “Natural Flotsam&Jetsam, with Evidence of its time in Saltwater, Tossed on The Tides and Ready to Be Found by the Casual Observer or Keen-Eyed Comber,” features her collections of: Syrian loofahs, ancient painted pumice stones found in Greece,  shells from Mexico and Australia, and driftwood from Washington state.  Yikes. We aren’t all such cosmopolitan (or well-traveled) collectors.

Nor are we all willing to institutionalize and formalize our collections, like the artist Claes Oldenburg, who

positioned various objects from his collection on a large storage unit and called it the “museum of popular art, n.y.c.†Although private, the display revealed the artist’s egalitarian attitude: both artworks and knickknacks were valid candidates for inclusion in the “museum.†Seven years later, in 1972, Oldenburg formalized this project and made it public at the international art exhibition Documenta, in Kassel, Germany. Mouse Museum includes 385 objects selected from his collection of more than a thousand items, housed in a structure based on “Geometric Mouse,†a recurring motif in his drawings, prints, and sculptures. The Ray Gun Wing extension followed in 1977. Unlike Mouse Museum, which contains a miscellany of things, Ray Gun Wing features 258 “ray gun†specimens, including brightly colored toy guns as well as found objects with the right-angled form of a pistol. Its architectural structure echoes the shape of the objects contained within.  (source: MoMA: Mouse Museum/Ray Gun Wing)

Between decor blogs, HGTV, and print media’s love affair with newly renovated Manhattan flats, the act of decorating one’s home or keeping a collection has begun to feel like a public-facing profession.  You curate things? Are you an artist, a designer, or an author?  But that’s not right.  You don’t have to turn a storage unit into a museum, write a book about your Greek pumice stones, or open a trendy boutique in Brooklyn for the act of collecting to be fulfilling and worthwhile.  Collecting can be a profoundly meditative pursuit, like beachcombing, or picking and pressing wildflowers.  It can also be thoughtful and effortful: Oldenburg accepted contributions for his “museum,” but took only those objects that matched some inscrutable mental template (cleverly imagined here as a script).  I do something similar when I’m beachcombing: I couldn’t say why one rock is worth picking up and another is not, but I’m definitely searching for something, and it requires a surprising amount of mental effort to sift through all the information flowing down my optic nerve.  As Sibella Court writes in Life of a Bowerbird, “Collections are simply an attraction (over & over again) to the same object, or shape, or color, or texture.”  Who knows what makes a given collector’s neurotransmitters fire, or makes all the looking worthwhile?

I think viewing a collection can also be a deeply intimate experience.  Looking over one’s own collections evokes memories of found patterns or themes, repeated in a multitude of variations.  It is an opportunity to discover still other patterns and connections you haven’t seen before.  And recognizing themes and patterns in someone else’s collection can be like seeing the world through someone else’s eyes — which is probably why Oldenburg’s installations are described as “offer[ing] the viewer the rare privilege of watching the artist see. . .”  (source: MoMA: Mouse Museum/Ray Gun Wing)

I love Sibella Court’s book, but because collections are very personal, I’ve concluded that I prefer Jennifer’s photographs: I relate so much more to the kind of searching they represent. Â I grew up beachcombing and yardsaling every summer, not visiting the shores of Crete. Â When I built forts or told myself stories, I used what I found around me: the odds and ends of adult projects, junk left out as trash, things I found in the basement or on a winter beach. Â These things were only as mysterious as I was curious; fortunately for me, I am very, very curious, so I always had more mystery than I needed.

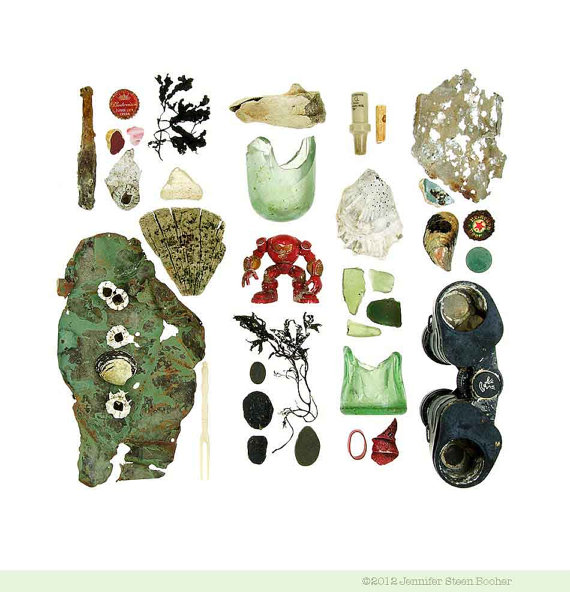

Beachcombing Series No. 56

8×8 print

Jennifer Steen Booher

And that’s why I relate to Jennifer’s work.  Hers is a playful kind of collecting. Jennifer criss-crosses rusty scissors like dueling blades in Scissors, Paper, Stone: a child’s makeshift Jolly Roger, perfect for nailing above a clubhouse door.  She arranges shark’s teeth in a heart.  And she seems to see nothing incongruous or portentous about placing a red action figure next to a broken bottle at least a century older, or a delicate frond of seaweed: each has its own natural history.  In her words:

Beachcombing is fundamentally a treasure hunt, an emotional and old-fashioned form of exploration that depends on serendipity, suspense, and glee. Identifying my finds can require research in marine biology, glass-making history, geology, chemistry and other disciplines. The resulting photos look vaguely scientific, with echos of pressed botany specimens and Linnean classification diagrams. In a way they are. But where most scientific illustrations present answers, these photos are a way of articulating my questions. [from “art for the insatiably curious.”]

Being a child is asking questions. Â Becoming an adult is choosing to answer some of those questions, and accepting that others may never be answered. Collecting is finding new questions to ask, answer, and abandon (you never want to run out of questions). And as Jennifer points out, making art out of one’s collections is one way of sharing your questions with other people. Â One can also share answers, of course; but I happen to like sharing questions better. Â And if that makes sense to you, you might like Jennifer’s work too.

More of Jennifer’s photography: her etsy gallery, her blog, and her website.  Buy prints of her work here.

Note: This review has been a very long time coming. Â I ran across Jennifer’s gallery on etsy over a year ago. After a few visits, I asked Jennifer if I could review her art and share some of her work; she graciously said yes, but I was so busy I never finished the review. Â (As many bloggers have noted, sometimes blogging feels like just another chore; I’ve been in that place this past year.) Â A few months ago, I was idly arranging some shells and beach glass I’d just collected; that reminded me of Jennifer’s art, and resolved to finish the post as soon as I got back from the beach. I put it on my to-do-list app, where it languished. . . three more months. I didn’t finish until today. So I thought Jennifer’s “Interrupted Pocket Watches,” below, would be a fitting coda to a review that suffered so many interruptions. Â So sorry for the delay, Jennifer.

Interrupted Pocket Watches

12×12 print

Jennifer Steen Booher

All artwork reproduced courtesy of Jennifer Steen Booher.