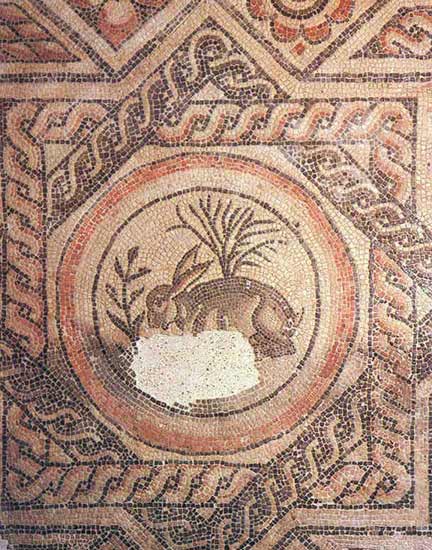

Hare Floor Mosiac

4th century

Corinium School, Cirencester, Gloucestershire

Corinium Museum

Dan Chiasson’s book of poetry, Natural History (2005) is inspired by Pliny (the Elder, who wrote the original Naturalis historia) and Horace. Taking Pliny as a starting point may well be hubris, because Naturalis historia is an encyclopedic history of everything, a curiosity cabinet of words, imperfectly balanced between imagination and observation. (Pliny, less reliable than he was prolific, warns of basilisks, dragons, manticores, and the catoblepas: “its head is remarkably heavy, and it only carries it with the greatest difficulty, being always bent down towards the earth. Were it not for this circumstance, it would prove the destruction of the human race; for all who behold its eyes, fall dead upon the spot.”) Horace, in turn, wrote the Ars Poetica. I conclude that Chiasson is not easily intimidated.

What I like about Chiasson’s poems (and one reason Pliny makes a fit patron) is that they meld without apology or self-consciousness the lyric and the quotidian, the romantic and the scientific. The effect is sometimes invigorating, as in “Love Song (Sycamores)”:

Stop there. Stop now. I calculated that

the number of birds singing

on any given morning

was a function of the sycamores plus my hangover.

Sometimes the mix of slang and classics is distressingly weird. And when a poem makes me feel weird, I sit up and take closer notice than when I find it beautiful. This collection may pose as an encyclopedia, with titles like “The Sun,” “The Pigeon,” and “The Elephant,” but it confuses far more than it explicates, layering references and voices on each other until I’m sometimes not quite sure who’s speaking. Chiasson addresses one poem to himself, mentions himself by name in another, mentions or references a dozen other modern poets. This is a book of poetry you’re reading, in case you forgot. As in a museum, it’s disorienting and a little annoying when the nose hits the glass.

Yet I’m charmed by my feeling that Chiasson is, above all, teasing. This is a poet at play, a poet unafraid to stitch his own idiosyncratic collage-history of the world (one of the poems I like most is called “Made-up Myth”). That history is sometimes panoramic, sometimes intimate:

They are made of such strange dreams, bee-like dreams:

a peach orchard she never played in as a child,

where overnight the peaches never turned to stone. (“Made-up Myth”)

My favorite of all Chiasson’s poems appeared in the New Yorker, but not in Natural History, so I have obtained his permission to reproduce it here in entirety. It’s a riff on, of all things, a Roman floor mosaic, which was discovered in 1971 in Cirencester, England. (Corinium Dobunnorum was the Roman name for Cirencester, second in size only to London in 2nd century Britain.)

For a glass lagomorph, the hare sure has a lot of opinions. The poem is panoramic in both space and time, crossing years and nations the hare, buried in forgotten Corinium, did not witness. Yet to me its voice rings familiar: resigned, cynical, a tad plaintive, wry. What difference does art’s commentary make in the end, buried or re-discovered? Does it exist merely to give us what Whitman calls “the certainty of others” – the awareness of our place in the long continuum of life and history?

“Mosaic of a Hare: Corinium”

The New Yorker

Dan Chiasson

The boats pulling in, the boats pulling out, the top-hat

commerce of the “infant century,” crowds, crowds,

“the certainty of others,” the bomb

that filled the air with horsehair and the ambulance after:why wouldn’t I hide in my little glass body? I have a clover sprig

made of glass to aspire to, with my glass appetite.

I raise certain questions about art and its relation to stasis,

yet I despise the formalists as naïve and ahistorical.Here’s my problem with America: this “would be” that obliterates

all other moods, playing over and over in people’s heads,

the abstract optative that destiny works out.

I don’t have the luxury to think in terms of destiny.What nobody seems to get about me is, though you’re made of glass

it doesn’t mean you don’t have appetites: I do. Or fears: I do.

The day the darkness took the whole basilica, I was afraid;

and equally afraid the day, centures later, they switched the lights on.Let rabbits think in terms of destiny: Whitman, the great

American rabbit poet, the rabbits in the government,

the rabbits that light and the ones that snuff out the fuse,

and all their pretty rabbit children, waiting to be casserole.

Notes – “the certainty of others” is from Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry“. If you’re confused by the last stanza, note that hares are different from rabbits. I’m not sure, but I think the bomb refers to the assassination of the Nazi Reinhard Heydrich in 1942, who died ironically not from the blast, but from septicemia induced by horsehair and debris released from the seat of his car.

4 Responses to Poem of the Week: Mosaic of a Hare